Dynamics of Drug Possession Charges in Illinois, from Investigatory Stops to Sentences

B A C K G R O U N D

Illinois is one of 18 states that makes possession of drugs (except cannabis) a felony in all cases.

This means that possession, even of very small amounts of drugs, can lead to serious criminal legal system involvement. Felony arrests lead to pretrial jail time, often because people are held on bonds that are unaffordable, and being convicted of drug possession can lead to a lifelong felony record. These felony convictions lead to thousands of long-term barriers to leading a successful, free life.

These consequences are particularly disproportionate with the possession of small amounts of drugs. When people possess small amounts of drugs, it is often an indication that they are a substance user – and that they may need referral to treatment and other services, but not criminal legal system involvement.

Drug laws are often touted as necessary to catch and prosecute drug “kingpins”; the legislative intent section of the Illinois Controlled Substances Act (720 ILCS 570/100) notes: “It is not the intent of the General Assembly to treat the unlawful user or occasional petty distributor of controlled substances with the same severity as the large-scale, unlawful purveyors and traffickers of controlled substances.” In practice, however, the brunt of Illinois’ drug law enforcement does fall on people who possess small amounts of drugs, not “large-scale” traffickers. These drug laws also disproportionately impact Black Illinoisans. In 2021, HB 3447 (Ammons/Bush) was introduced in the Illinois House. That bill would make possession of small amounts of substances a misdemeanor, rather than a felony. To get a sense of how that bill might affect drug arrests in Illinois, we looked at the dynamics of drug seizures, arrests, convictions, and incarcerations. We sought to explore (1) what quantities of drugs were involved in seizures of drugs in traffic and pedestrian stops and in arrests; (2) whether drug arrests and seizures were occuring in a racially disproportionate manner; (3) how initial charges in low-level possession cases chosen by police and prosecutors affected case outcomes, and (4) how much money county and state governments spend on incarcerating people for possessing small amounts of drugs. To do so, we examined data from five sources (see Methodology section at the end of this report for full details): the Investigatory Stop Report data for the state of Illinois (2016 to 2019), the publicly- available dataset of all adult arrests made by the Chicago Police Department (2014 to 2022), the admission and release data from the Cook County Sheriff’s Office (for 2021), and the publicly-available Illinois Department of Corrections (IDOC) admissions data for (2018 to 2021) as well as the Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority’s “Prison Admissions for Drug Offenses” dashboard (prior to 2018).

The analysis brought a number of valuable insights, which are detailed below, including: (1) police in Illinois rarely find large amounts of – if any – drugs during pedestrian and traffic stops; (2) most drug arrests are for low-level drug possession, not for dealing; (3) Illinois’ Black communities are disproportionately impacted by searches for drugs; (4) the over-charging of people who are alleged to possess drugs increases the punishment for their actions and contributes to over-incarceration; and (5) sentencing and imprisonment for drug-related issues are costly to counties and the state.

F I N D I N G S

Pedestrian and traffic stops rarely lead to law enforcement finding drugs – and when they do, usually lead to seizures of only small amounts of drugs.

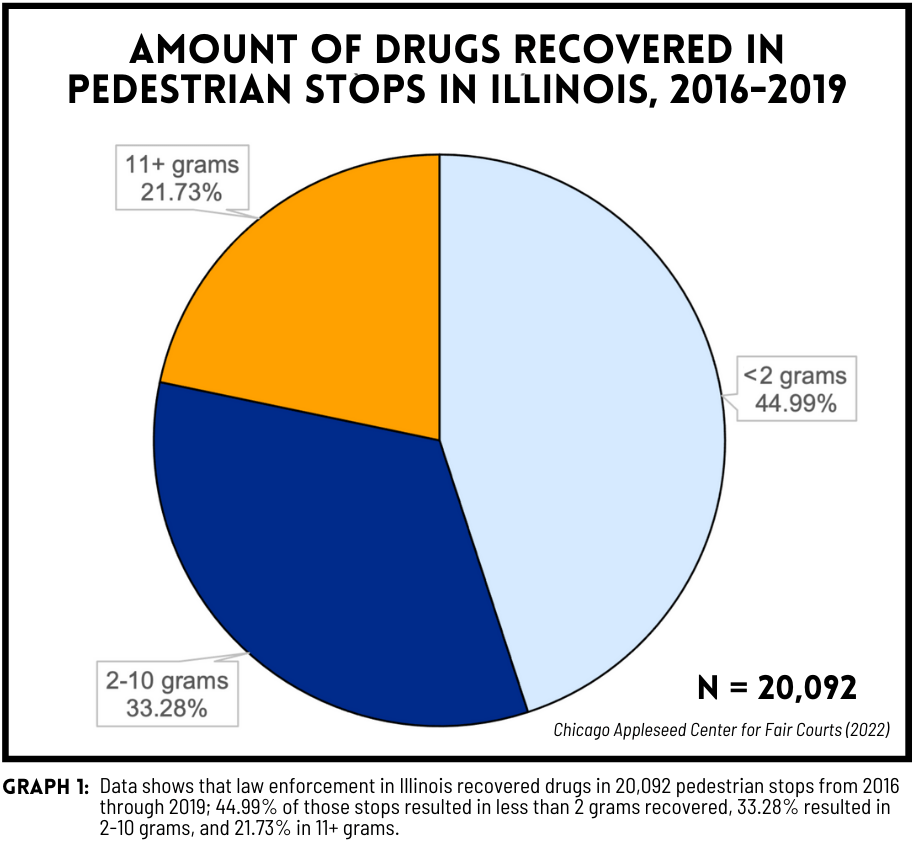

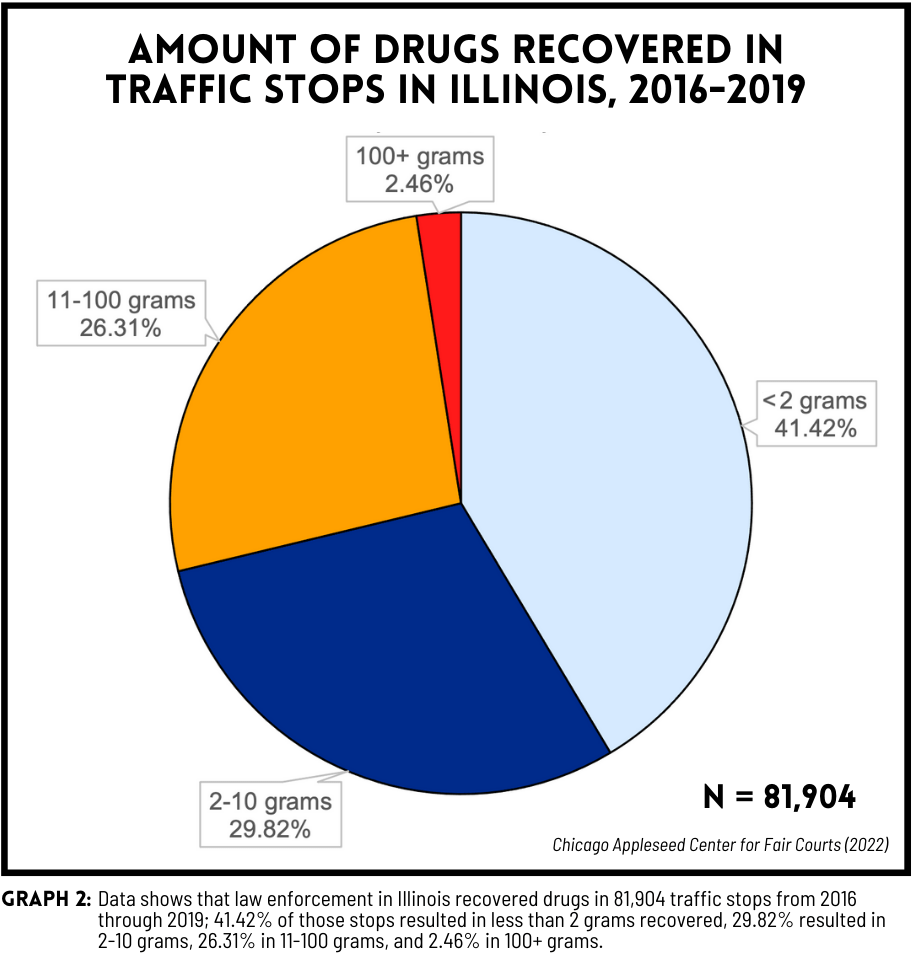

Illinois law enforcement agencies make millions of stops of cars and pedestrians each year. In most of these stops, police do not search people or their belongings. But in the small minority of cases where they do search people’s things, police find drugs in only about 1-in-5 traffic stop searches (22%) and about 1-in-6 pedestrian searches (16%). Usually, the amounts of drugs that are found are small. In 45% of pedestrian searches where drugs were recovered and 41% of traffic searches where drugs were recovered, police found under 2 grams of drugs – less than a standard sugar packet’s worth.

In 78% of pedestrian searches where drugs were recovered and 71% of traffic searches where drugs were recovered, police found 10 grams of drugs or less – an amount that is less than a tablespoon.

Out of about 8.5 million traffic stops made by police in Illinois from 2016 through 2019, only about 28,000 recovered more than 10 grams of drugs – 0.3% of all stops. Only 0.9% of pedestrian stops resulted in finding more than 10 grams of drugs. It is even rarer for police to find large amounts of drugs – traffic stops only recover more than 100 grams of drugs in 0.02% of stops.

These numbers show that traffic stops and pedestrian stops primarily drive people who possess small amounts of drugs into the criminal legal system. This is important, as our findings challenge a common misconception that traffic stops regularly intercept large amounts of drugs moving to dealers to be sold in drug markets. Instead, police are mostly stopping and arresting people likely to be users of substances who are carrying a small amount for personal use, rather than “drug kingpins.” In reality, big busts of drugs from traffic stops are exceedingly rare.

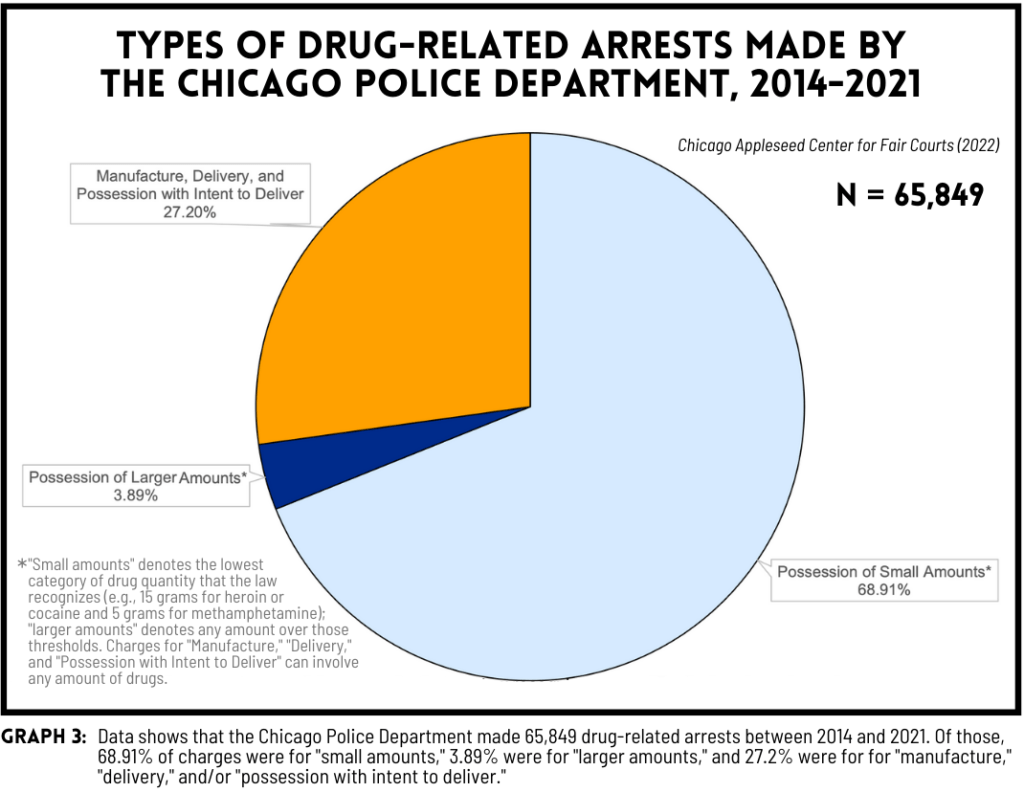

Most drug arrests are for low-level drug possession, not dealing.

The city of Chicago is similar to the state as a whole in terms of arrests for drug-related allegations. Data from over 540,000 arrests by the Chicago Police Department between 2014 and 2021 show that about 66,000 arrests – about 12% of all arrests during that time – are for behavior criminalized under the Illinois Controlled Substances Act or the Methamphetamine Control and Community Protection Act. These laws criminalize the distribution, manufacturing, and possession of all illegal drugs. Although these laws may have been designed to target people who sell drugs, most arrests made by Chicago Police are made for possession of relatively small amounts of controlled substances.

Illinois has 5 classes of felony charges. The lowest level felonies are Class 4 (punishable by probation or 1-3 years in prison), followed by Class 3 (punishable by probation or 2-5 years in prison), Class 2 (punishable by probation or 3-7 years in prison, Class 1 (punishable in rare cases by probation; usually by 4-15 years in prison, and Class X (punished by 6-30 years in prison; no possibility of probation). In Illinois, it is a Class 1 felony to possess certain quantities of controlled substances – most commonly, more than 15 grams of heroin or cocaine (See 720 ILCS 5/570-402(a)(1) and 720 ILCS 5/570-402(b)(1)). Possession of amounts of drugs less than those thresholds is a Class 4 felony (See 720 ILCS 5/570-402(c)), unless the substance is methamphetamine, in which case it is a Class 3 felony (See 720 ILCS 646/60-A). Distribution, manufacture or possession of drugs “with the intent to deliver” them carries harsher penalties (See 720 ILCS 5/570-401).

Over two-thirds of arrests that the Chicago Police Department made between 2014 and 2021 were for possession of the smallest quantity category of drugs, with only 27% of drug arrests involving allegations of drug distribution or the manufacturing of drugs.

These analyses reinforce the findings from our traffic stop data analyses above: most people who are arrested for drug-related charges are arrested for small-scale possession. This suggests that the enforcement of drug laws is primarily affecting people who use drugs, and certainly not the “kingpins” that drug laws attempt to target.

Searches for drugs disproportionately impact Illinois’ Black communities.

Although there is no evidence that White and Black people use or sell drugs at different rates, both pedestrian/traffic stops and arrests are highly disparate in terms of their impact on Illinois’ Black communities.

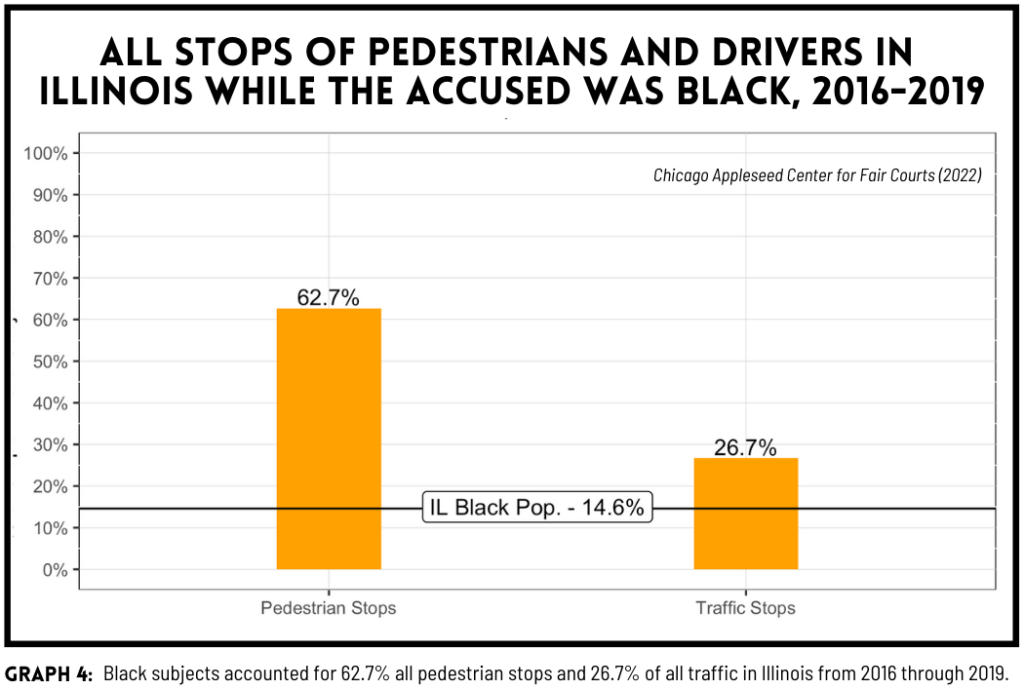

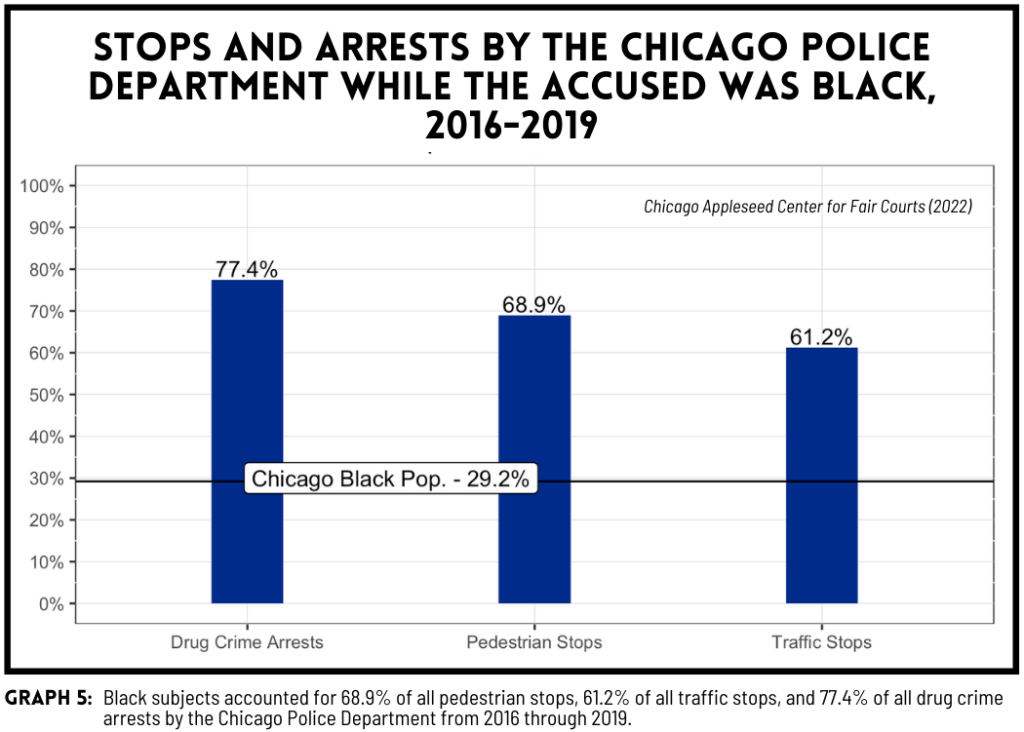

While only 14.6% of the state population is Black, Black people make up 62.7% of pedestrian stops and 26.7% of traffic stops. In Chicago, Black people make up 29.2% of the population, but are involved in 61.2% of traffic stops, 68.9% of pedestrian stops, and 77.4% of all drug crime arrests.

The Federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSA) 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, which published the most recent data available, found that 3.4% of White people and 2.9% of Black people reported selling drugs in the past year (it’s important to note that this study likely undercounts drug use and selling rates, since it is a government sponsored survey and respondents may have under-reported because of stigma and fear of prosecution). There is no statistically significant difference between races in rates of reported drug use. The difference in enforcement, then, likely falls disproportionately on Black communities because of racist policing patterns rather than because of differences in behavior.

Over-charging people who possess drugs increases the punishment for their actions and contributes to over-incarceration.

Although many people arrested for drug allegations are found with small amounts, they are not always charged with low-level “possession of a controlled substance.” Depending on the choices made by police and prosecutors, people can be charged with “possession with intent to deliver” instead of just “possession,” which leads to harsher sentences. Illinois statute groups “possession with intent to deliver” with “delivery” and “manufacture” of drugs, so that people charged with “possession with intent” face the same consequences as people charged with giving or selling drugs to another person. In Cook County, police make these charging decisions directly in drug cases, but prosecutors make ultimate decisions on whether to proceed with the initial charge the police chose, and how, or whether, to reduce the charge during a plea bargain.

The concept of “intent to deliver” has been broadly interpreted by courts, with factors that apply to nearly everyone, such as having a cell phone (People v. Thomas, 2019 IL App (2d) 160767 at P24), as well as factors that apply to many people that use drugs, such as having paraphernalia (People v. Berry 198 Ill. App. 3d 24 at 29, (1990)), being considered evidence of intent. For this reason, an individual charged with possession of the lowest quantity category of drugs could be charged with anywhere from a Class 4 felony (lowest class of felony) to a Class 1 felony (second highest class of felony) depending on the location of the arrest and whether the police and prosecutors decide to allege that there was intent to deliver (See 720 ILCS 570/402(c) and 720 ILCS 570/401(d) and (e)). For the sake of brevity, we will refer to charges for “manufacture or, delivery, or possession with intent to deliver a controlled substance” under 725 ILCS 570/401 as “delivery/possession with intent.”

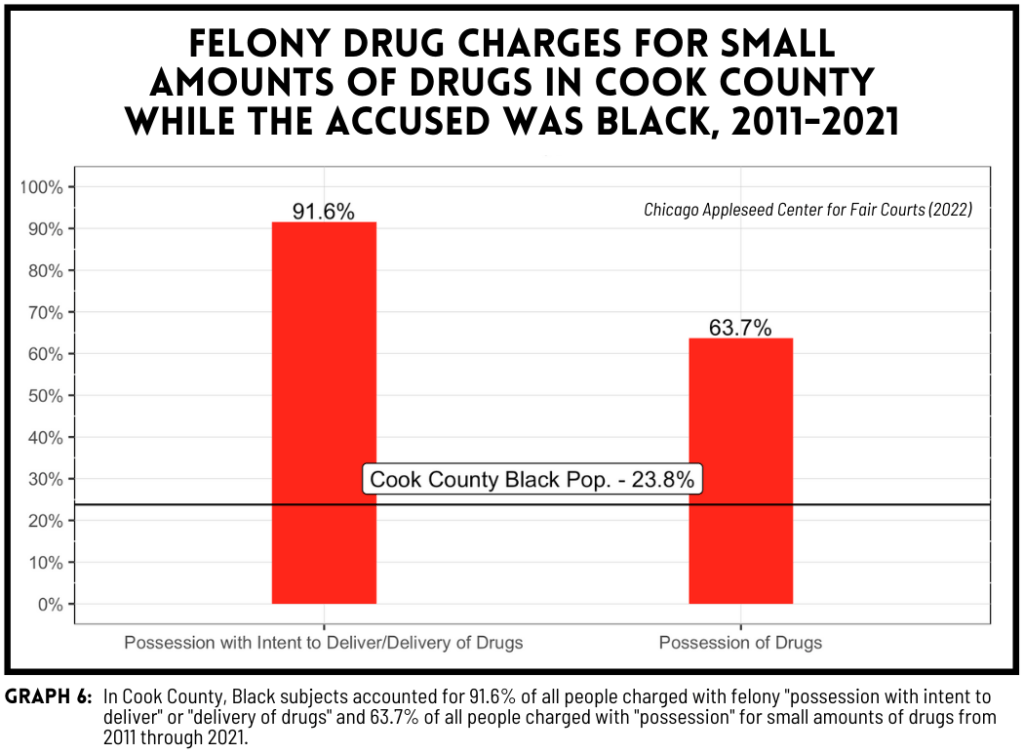

For charges for “delivery/possession with intent,” notably, charges fall much more disproportionately on Black Cook County residents than do simple “possession” charges.

A shocking 91.6% of people charged with “delivery/possession with intent” were Black, compared to 23.8% of the overall Cook County population. Charges for drug possession were also extremely disproportionately levied against Black Cook County residents; 63.7% of charges for possession were against Black people.

Because of the way Illinois defines its drug laws, it is impossible to tell from data how many “delivery” and “possession with intent” charges are, in fact, criminalizing the behavior of selling or giving drugs to another person, and how many involve only possession of drugs. However, one clue to the issue lies in plea bargaining. Many people charged originally with “possession with intent to deliver” charges eventually end up pleading guilty for simple “possession” charges. About 43% of “delivery/possession with intent” charges in Cook County eventually plead to a “possession” charge.

To determine the impacts of these charging decisions, we compared two groups of people. The “Initial Possession” group were initially charged with Class 4 simple “possession,” and eventually pleaded to that same charge. The “Initial Enhancement” group were originally charged with Class 1 or 2 “delivery/possession with intent to deliver” charges, where small amounts of drugs were found, but eventually pleaded to reduced charges of Class 4 simple “possession.” We found that:

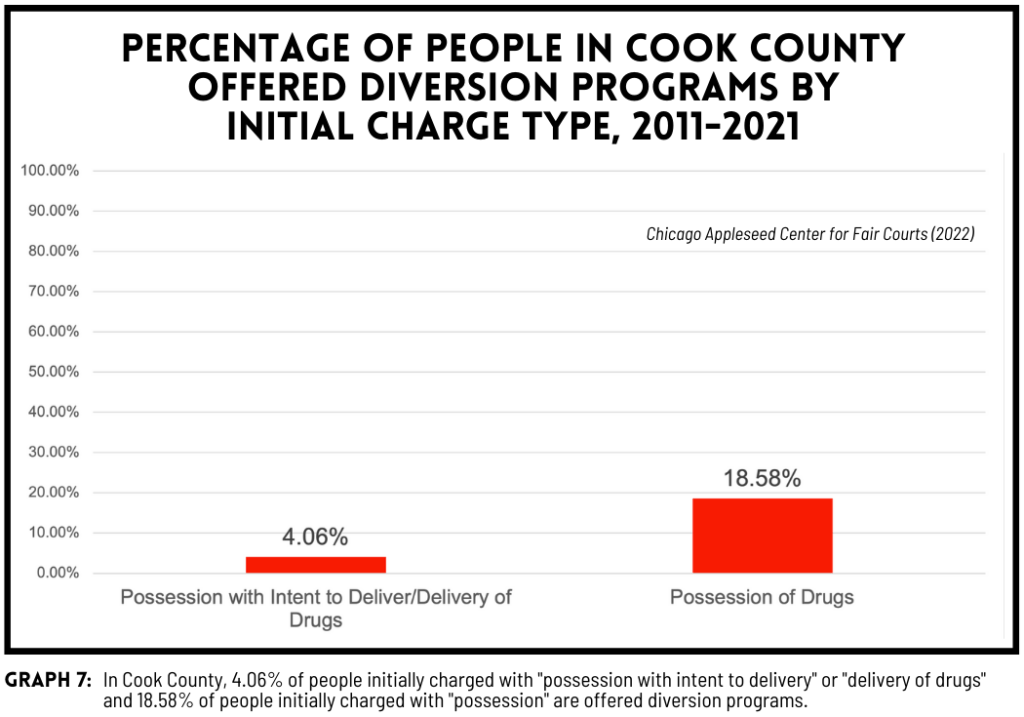

- The “Initial Possession” group had more lenient outcomes in their cases than the “Initial Enhancement” group. They received probation sentences 55.12% of the time, while the “Enhancement” group received probation only 28.77% of the time.

- When people from the “Initial Possession” group were sent to prison, they served shorter sentences than the “Initial Enhancement” group. People in the “Initial Enhancement” group were 2.6 times more likely to face more than a year in prison for their case.

- People in the “Initial Possession” group were given more access to diversion programs than the “Initial Enhancement” group, with 18.58% of people in the “Initial Possession” group diverted, while only 4.05% of people in the “Initial Enhancement” group were.

Importantly, racial inequities in prison sentences persisted no matter what a person was initially charged with. White people in both the “Initial Possession” and “Initial Enhancement” group were less likely to be sent to prison (28.78% and 44%, respectively) than Black people (50.79% and 71.47%, respectively).

In the current system, allowing police and prosecutors to choose whether to charge “deliver/possession with intent” or simply “possession” when the initial police encounter for most people charged involves only small amounts of drugs ultimately increases penalties for people charged with drug “possession and decreases access to diversion programs. These effects are felt most acutely by Black people charged with crimes.

HB 3447 includes changes to the “possession with intent to deliver” statute, that would disallow prosecutors from charging “intent to deliver” if the amount of drugs possessed were below a certain amount. Prosecutors could still charge manufacture or delivery of drugs charges for those small amounts, and in situations where a person is alleged to have started but not completed a drug transaction, attempted delivery charges are available. These changes would make sure that everyone charged with simply possessing small amounts of drugs – no matter whether they fit certain characteristics like having money or paraphernalia on their person – would be charged with the same crime: misdemeanor “possession of a controlled substance.” These changes would prevent the disparities in diversion opportunities and sentencing caused by prosecutors charging “deliver/possession with intent to deliver” charges in cases where ultimately they agree that the appropriate charge is simple “possession.”

Sentencing and imprisonment of people for drug charges costs counties and the state.

Although sentences of imprisonment for possession charges are becoming less common in Cook County (346 people were sent to prison for possession charges from Cook County in 2019, compared to 1,487 in 2012), imprisonment for drug possession charges, both before and after conviction, still costs Illinois taxpayers millions of dollars each year.

Cook County imprisoned 751 people in Cook County Jail in 2021 whose highest charge was a Class 4 “possession of a controlled substance” or Class 3 “possession of methamphetamine.” Overall, those people spent a minimum of one and a maximum of 306 days in jail in 2021, totaling a collective 24,424 days in jail. The Illinois Sentencing Policy Advisory Council (SPAC) has calculated the approximate cost of incarcerating someone in Illinois jails in 2021 was $40,567 annually, or about $111.14 per day.

Assuming that Cook County jail costs are approximately commensurate with the state average, this means that Cook County spent more than $2.7 million incarcerating people pretrial for “possession of a controlled substance” allegations.

The costs of incarcerating people sentenced to prison for simple possession cases is similarly high. Between 2018 and 2021, the Illinois Department of Corrections records show that 4,479 people were sentenced to incarceration and served time in prison for low-level possession charges. IDOC also projected the total amount of actual days those people would spend in prison on these charges; it amounts to over 1.2 million days collectively, or almost 3,500 years in prison. Based on SPAC’s calculated the costs of a year of IDOC incarceration for 2018, 2019, and 2021, the costs to imprison people during this time was $54,351 per year.

Illinois spent, on average, a total of over $157 million incarcerating people admitted to IDOC for simple possession charges between 2018 and 2021 based on these calculations.

Cook County is the county that sends the most people to state imprisonment each year. Overall, the number of people being incarcerated in IDOC for drug-related crimes is falling in Cook County; however, in Central and Southern Illinois, admissions to IDOC for drug-related charges are actually rising, driven largely by an increase in incarcerations for possession and delivery of methamphetamine charges in those areas. Between 2015 and 2019, imprisonments for drug-related charges in Southern Illinois rose 56%; in Central Illinois, they rose 21%. These rebounding numbers of prison sentences, at a time when the number of people being sent to prison statewide is decreasing, mean that Illinois may be spending millions of dollars incarcerating people for possessing small amounts of drugs for years to come.

C O N C L U S I O N

Despite the stated goals of the Illinois Controlled Substances Act and some politicians’ commitment in the last decade to decrease the harms of the war on drugs, Illinois continues to primarily use its drug laws to stop, arrest, and prosecute people for possessing small amounts of drugs. Illinois must change its penalties to reduce the harm caused by these arrests and prosecutions of people likely to be substance users, so that felony prosecutions and convictions are not a barrier to people getting the treatment and support that they want and need.

Our research confirms that the burden of Illinois’ drug laws fall most heavily on Black Illinoisans, who are more likely to be stopped, arrested, and sent to prison for drug possession charges and are more likely to be charged with more severe “possession with intent to deliver” charges than White Illinoisans.

Illinois spends millions every year on processes that are systematically hurting Illinoisans – especially Black Illinoisans – and saddling them with incarceration and felony convictions for possession of less than a tablespoon of drugs. It is time for Illinois to modernize our system and make the change necessary to reduce penalties for drug possession.

M E T H O D O L O G Y

This analysis looks at a number of data sources to determine who Illinois’ drug laws are targeting and prosecuting the most:

- The Investigatory Stop Report data for the state of Illinois from 2016 to 2019. Since 2003, the Illinois Department of Transportation has collected data on traffic and pedestrian stops by law enforcement agencies in Illinois. The data is collected primarily to study racial bias in traffic and pedestrian stops. The investigatory stop data also includes notation each time drugs are recovered from a car or pedestrian and how much was recovered. The dataset does not encompass every traffic and pedestrian stop in Illinois, because only about 80% of law enforcement agencies reported their stop data to the Illinois Department of Transportation. After limiting the data to 2016-2019 to get a sample of stops unaffected by the COVID-19 pandemic, we separated stops into categories based on the amount of drugs found. In pedestrian stops, the data had only five categories: <2 grams, 2-10 grams, 11-50 grams, 51-100 grams, and >100 grams. In the traffic stop data, the data recorded the amounts of drugs found through different kinds of searches – searches of the vehicle, searches of the person of the driver and passenger(s), or searches by drug-sniffing dogs. We combined these amounts into similar categories, counting amounts within ranges in such a way as to assume that the maximum amount of drugs was found; for example, when an entry said that 2-10 grams were found in the vehicle, 2-10 in the car, and 2-10 by drug-sniffing dog, we recorded the amount as 11-50 grams, since the amount could have been above 10 grams, even though it also could have been under 10 grams. As a result, our calculations of the amount of drugs found may overestimate the amount of drugs found, but are not underestimates. It is also important to note that these data do not differentiate what kind of drug was recovered, which means that cannabis, as well as other narcotics such as heroin, are included in these totals.

- The publicly-available dataset of all adult arrests made by the Chicago Police Department (CPD) between 2014 and 2022. After limiting the data to 2014-2021 to encompass only full years of data, we tagged cases where people were arrested for all drug cases and where people were arrested specifically for drug possession cases, using the statute numbers of the charges listed in the dataset, and compared the relative prevalence of each category of charge.

- Publicly-available data on charging, disposition, and sentencing decisions made in the Cook County felony courts. These data are maintained and updated regularly by the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office (CCSAO). Because charges for methamphetamine are defined differently and have different charge levels than charges for other non-cannabis controlled substances, we looked only at non-methamphetamine, non-cannabis charges(i.e., those criminalized under the Illinois Controlled Substances Act). After isolating the specific Administrative Office of Illinois Courts charge codes that corresponded to Class 4 “possession” of an amount of a controlled substances below certain amount thresholds (charges under 720 ILCS 570/402(c), Class 2 “delivery/manufacture/possession with intent to deliver” an amount of a controlled substances below certain amount thresholds (charges under 720 ILCS 570/401(d), and Class 1 “delivery/manufacture/possession with intent to deliver” an amount of a controlled substances below certain amount thresholds within 500 feet of a school (charges under 720 ILCS 570/407(a)(2)), we joined the initiation entries for those charges to the disposition, diversion, and sentencing tables to compare how outcomes differed between charges that began as Class 1 or 2 charges and ended as Class 4 “possession” charges (which we called the “Initial Enhancement” group), and those that started and ended as Class 4 “possession” charges (which we called the “Initial Possession” group.

- Admission and release data from the Cook County Sheriff’s Office (CCSO) detailing the charges and number of days spent in custody for each person admitted to Cook County Jail in 2021. These data were obtained via a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request.

- Publicly-available Illinois Department of Corrections Admissions Data for 2018, 2019, 2020, and 2021. We also obtained data from the Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority (ICIJA)’s “Prison Admissions for Drug Offenses” dashboard to determine regional admission patterns prior to 2018. In analyzing the 2018-2021 data, we used ICJIA’s groupings of Illinois counties into South, Central, North (minus Cook County), and Cook regions so that comparisons between the dashboard numbers and the 2018-2021 IDOC data would be accurate. In looking at IDOC admissions, we looked only at people sentenced for drug possession charges who were serving their initial sentence, and excluded those spending time in prison for violating the terms of their mandatory supervised release.