We analyzed 536,000 CPD arrest records spanning a period from 2014 to 2020. Here’s what we found.

INCOMMUNICADO DETENTION

Arrested and deprived of communication without being charged with a crime — incommunicado detention in Chicago.

In film and on TV, stories about police and criminals have long made for captivating story lines and entertaining ways to stream episodes until 4 am. In a typical police drama, a crime is committed, the police make arrests, charges are filed, and the rest plays out in court — all conveniently within the confines of our short attention spans. However, in reality, after police make an arrest, people sometimes wait hours before getting booked and days before getting charged. The drama seems exciting but reality is a different experience.

How long can police hold someone without charges, legally speaking? How long are people held, in real life? Like any complex question, there are different ways to look at the question, legally, morally, and practically — this story starts from a legal perspective and explores the data behind arrests.

NO LIMIT HOLDING

There is a common perception that a hard-line legal limit to how long police can detain someone without charges exists; however, there is no limit, according to Illinois Legal Aid Online. For emphasis — according to Illinois state law, there is no defined legal limit to how long police can hold a person without charges. Instead, the ‘limit’ is a patchwork of Federal law and common police practices.

According to the Chicago Tribune, the topic of incommunicado detention has been an issue since at least 2003. In a Tribune article, “City Police Review Time in Custody,” the tangible legal limit is in the form of a 1991 U.S. Supreme Court ruling that places a limit of no more than 48 hours with the exception for an “extraordinary circumstance.” Although the 1991 U.S.C. case is the most recent, it actually updates a previous U.S.C. ruling in the Gerstein case regarding “extended restraint of liberty following arrest.” When combined, the result is a ‘soft’ Constitutional limit on total length of detention at 48 hours. However, at the state-level – nearly 20 years later in 2020 – the issue still remains at-large.

In this article, Chicago Appleseed and the Chicago Council of Lawyers share the initial phase of a living analysis on arrests and court proceedings in Chicago. The organization’s recently-obtained access to detailed arrest data in the Chicago Data Portal provides us with the ability to look into when people were arrested and how long they spent in custody, in order to examine patterns of the Chicago Police.

GETTING STARTED

This project started on October 14, 2020, and the charts cover the analysis through November and December 2020. At the time of this writing — after cleaning, organizing, and exploring the data — we initially have more questions than answers to share, and more questions than when we started.

The following sections provide charts and brief analysis of the numbers with a primary focus on average holding times from arrest to release. For instance, for how long is the average person handcuffed before booking at a police station? How long before they are charged with a crime? In relation to incommunicado detention, how long are the longest holding periods?

AVERAGE ARREST HOLDING TIMES

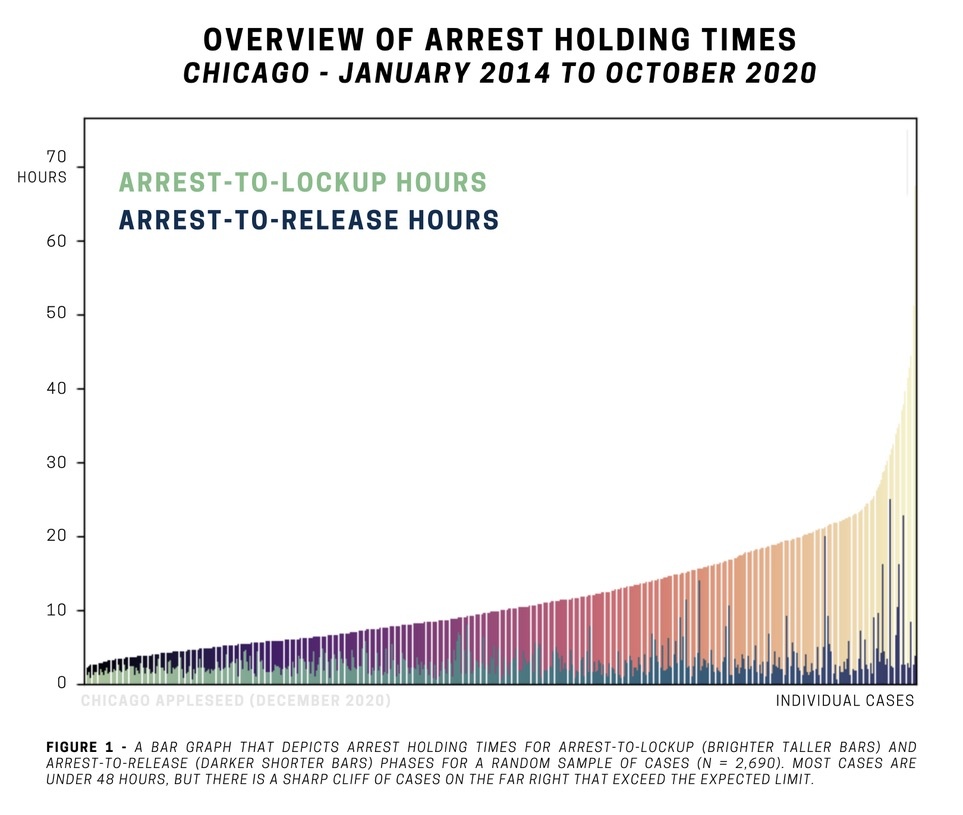

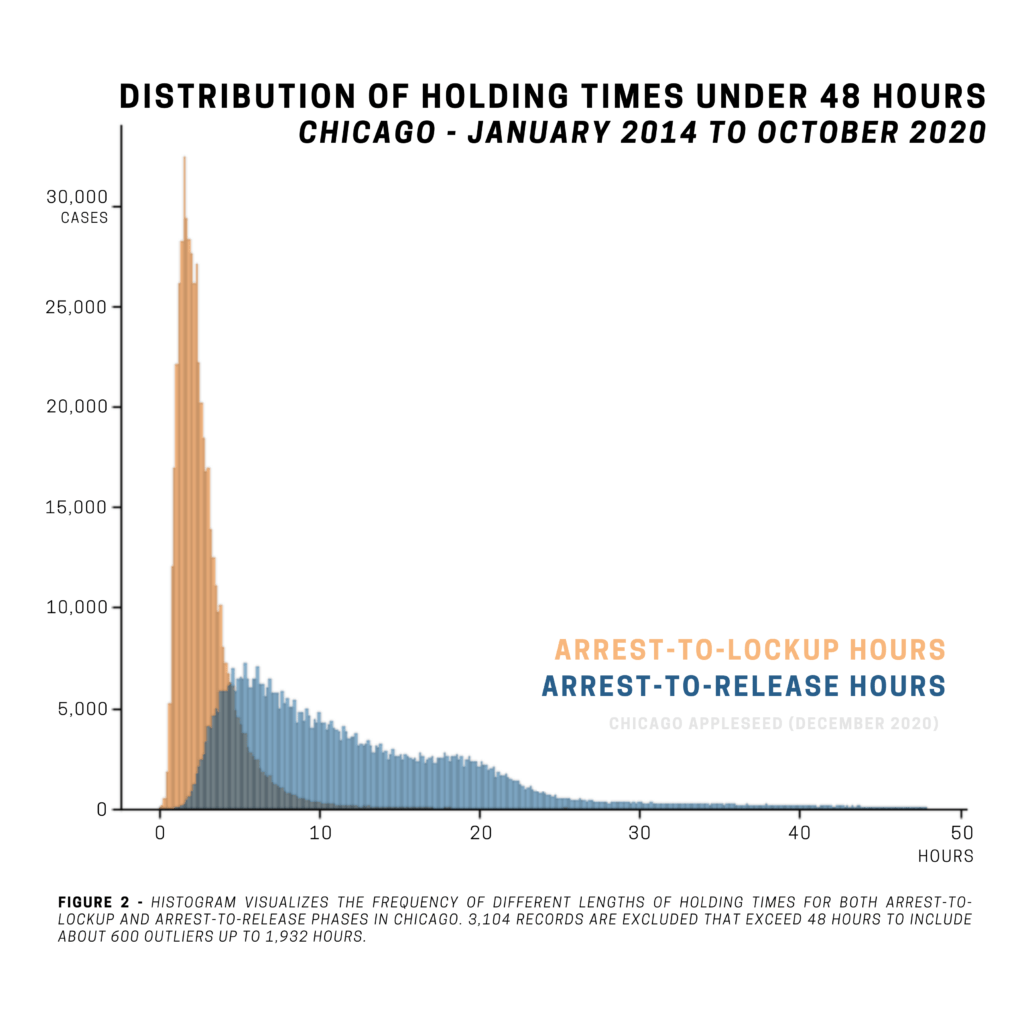

If police are allowed to hold people for over 48 hours in only extreme cases, how long are people actually being held for, on average? Unfortunately, the truth is unclear and the answer depends on how you slice the data. We started by considering two ‘phases’ of detention in this analysis: (1) the period from initial arrest to booking, or lockup, in the police station, and (2) the period from initial arrest to release from lockup. Based on a dataset of approximately 536,000 records, we encountered a few interesting points:

- Arrest to Lockup – Average of 2.8 hours: Generally, the length of time people spend in the back of a patrol car, from arrest to booking at the police station, is 2 hours and 48 minutes (2.8 hours).

- Arrest to Release – Average of 12.2 hours: The overall period from arrest to release from lockup is, on average, 12 hours and 12-minutes (12.2 hours), and usually coincides with a visit to bond court the next day.

Our findings show that, for the most part, these conclusions are what you might expect. For instance, the arrest to lockup times are, on average, just a few hours long; this makes sense simply because of traffic — how long does it take to drive anywhere in Chicago? Similarly, the overall time from arrest to release is about half-a-day, which indicates that most people are booked and then released after a court visit within the next day.

EXCEPTIONAL ARREST HOLDING TIMES

In Chicago, most arrest holding times are within the 48-hour limit. However, what should we, or can we, make from those few cases that fall into “exceptional” categories? After combing through the numbers, the news is not very good at all. In some cases, data suggests that police take up to two full days to book people at the station. Are these simply paperwork errors, or is something else lurking in these detention times?

- Arrest to Lockup – 6,282 cases of people held longer than 10 hours, for a maximum of 2 days: A 10-hour road trip feels like forever; but a 10-hour trip, handcuffed, in the back of a patrol car would feel like an eternity. Why does the Chicago Police Department (CPD) take so long with some cases, while most take 3 hours?

- Arrest to Release – 3,103 cases of people held longer than 48 hours, for a maximum of 4 days: After spending a night in lockup, most people will leave the next day on something called the ‘bond bus,’ which is a regular shuttle to the courthouse. In some cases, people might miss the bus, depending on the time of day they are arrested. However, it is unclear what “exceptional” circumstances have caused police to hold thousands of people for longer than 48 hours.

According to the data, in more than 99% of all cases, Chicago police hold people for less than the threshold; however, there are thousands of other cases that troublingly go for hours — or even days — past 48 hours from the initial point of arrest.

INTO THE CHARGE

The ability to strip a person of their liberty and freedom is incredible power. Much like a pistol or tazer, the power of arrest is one of many tools that police can choose to deploy at any given moment to exert power over someone else. However, unlike police shootings, which often end in explosive tragedy, arrests take place daily with little fanfare. But, despite their seemingly mundane nature, the power of arrest is incredibly important to check. As the New York Times once quoted, “pulling someone off the streets and putting him in jail for 36 hours without any showing of probable cause goes against basic American principles.”

To better define Constitutional protections in cases of arrest, a series of U.S. Supreme Court rulings created a soft limit of 48 hours with a set aside for exceptional cases. The 48-hour rule is a compromise between opposing interests. On the one hand, people have Constitutional protections that once arrested, they have a right to be charged with a crime or released as soon as possible. On the other hand, the system is overburdened and police work, like any other work, has its share of inefficiencies.

Although the soft limit of 48 hours is a step in the right direction to protect Fourth Amendment rights, the exact criteria for holding people longer than 48 hours remains undefined. For instance, in its rulings, the Supreme Court did not define what an “extraordinary circumstance” might be, and as a result, police have very wide discretion. Our analysis of CPD data demonstrates, to an extent, how police exercise this discretion.

MAKING SENSE OF CHARGES

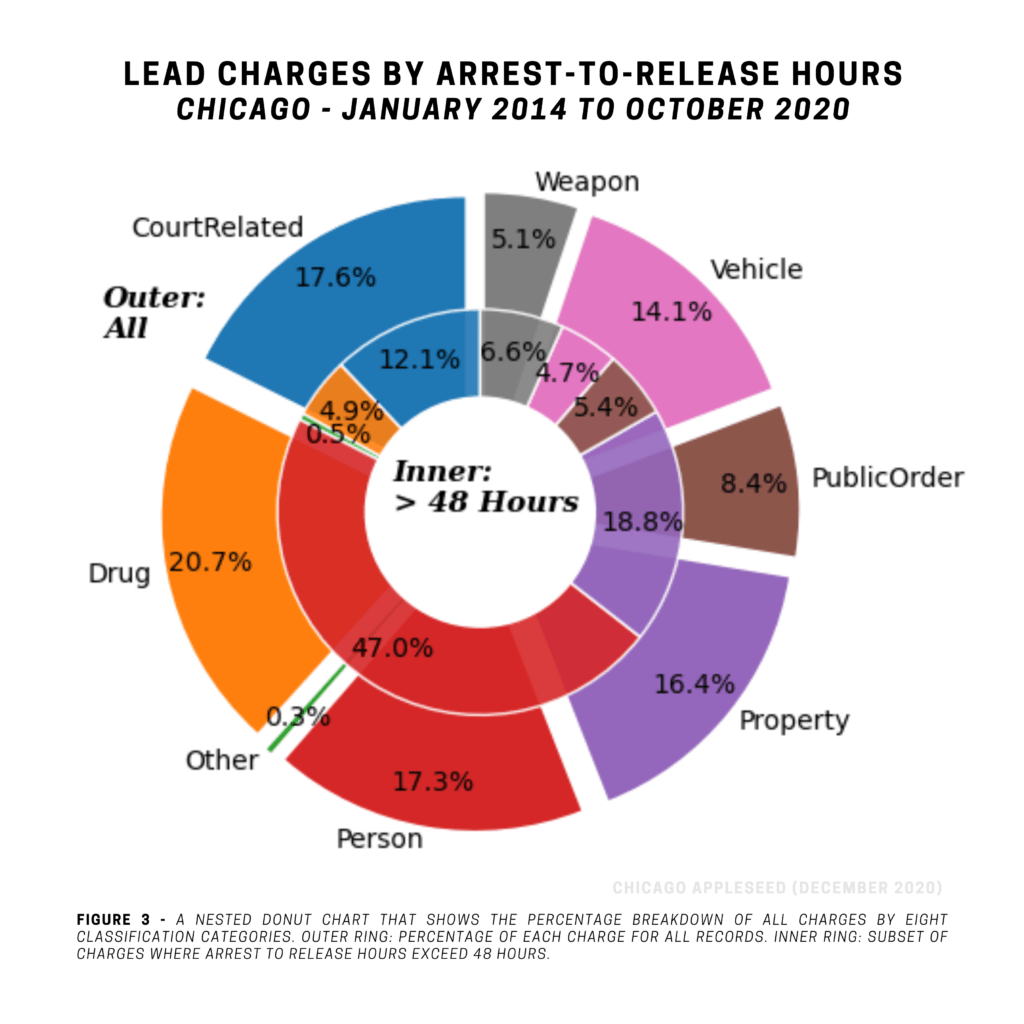

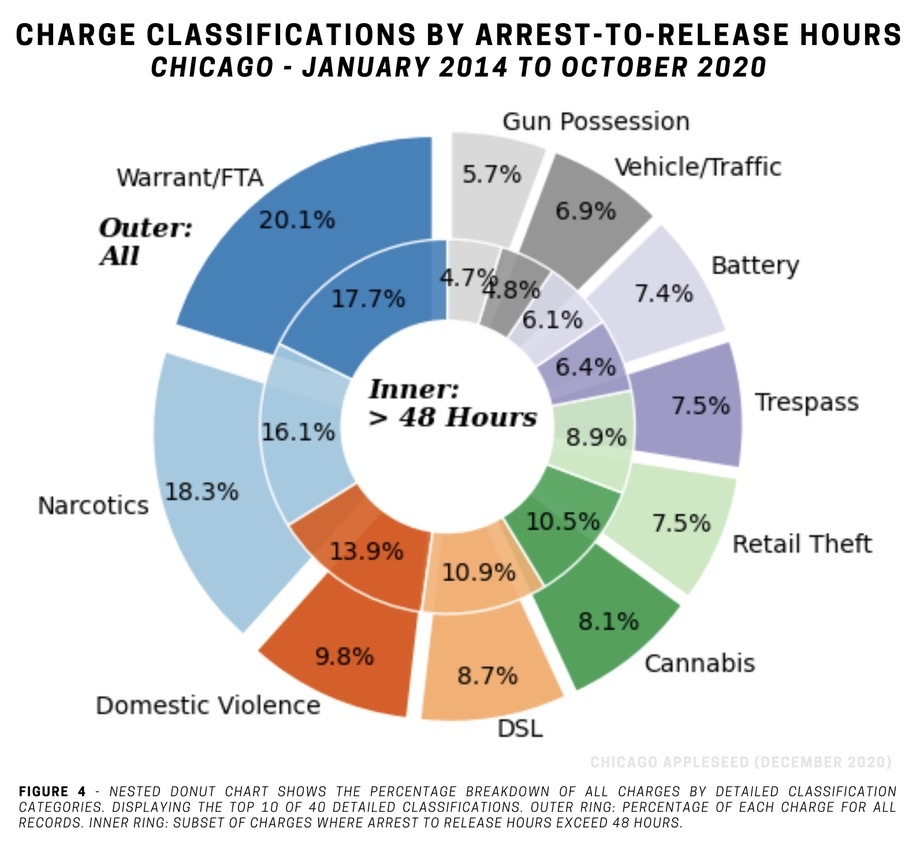

To understand what constitutes an extraordinary case, we first wanted to find what the data says about the average case. In the preceding donut chart, we classified thousands of unique charge descriptions into eight high-level buckets: Warrants/Failures to Appear (FTA), Gun Possession, Vehicle/Traffic, Battery, Trespassing, Retail Theft, Cannabis, DSL, Domestic Violence, and Narcotics. Drug charges (Narcotics and Cannabis) accounted for most cases overall, followed closely by court-related (Warrants and FTA) and property (Trespass and Retail Theft) charges. When the same data is filtered for holding times longer than 48 hours, battery and assault (“person charges”) account for about 50% of all cases. Similar to the high-level breakout, subcategories of “person” and “court-related” charges account for most cases; this analysis focuses primarily on a classification of these lead charges.

Based on an analysis of lead charges by arrest to release times, the finding may be two-part. At a high-level, ”person charges,” or those allegations commonly associated with violence against another person are more likely to be considered extraordinary and subject to holding times greater than 48 hours. However, at a more detailed level, there does not appear to be a meaningful difference in holding times by charge. In other words, based on a classification of lead charges, it is unclear what types of charges constitute an extraordinary case subject to excessively long holding times.

CHARGES BY RACE

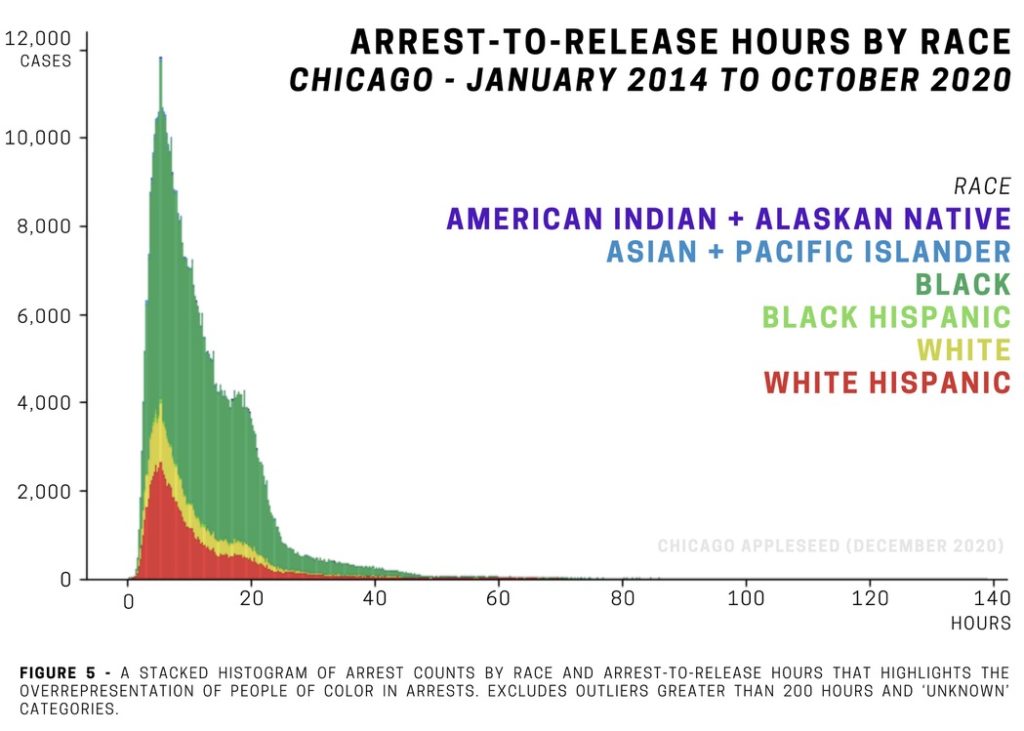

If the lead charge classification does not define an extraordinary case, then what else might explain the difference? Based on an initial analysis, when arrest-to-release hours are categorized by race, the data across all racial categories all have similarly skewed distributions [See Figure 5]. In other words, race, alone, does not initially appear to explain differences in holding times.

Although race does not appear to fully explain the difference in holding times, the data seems to demonstrate that people of color – overwhelmingly Black people – are overrepresented in arrests when compared to the general population. Likewise, individuals classified as “American Indian/Alaskan Native” and “Asian/Pacific Islander” make up less than one-percent of all cases. As a result, when we investigate the longest holding times (those times in the right tail in Figure 5), we may find that there are more people of color arrested for extreme periods simply because they comprised a higher percentage of the arrested population.

CHARGES BY POLICE DISTRICT

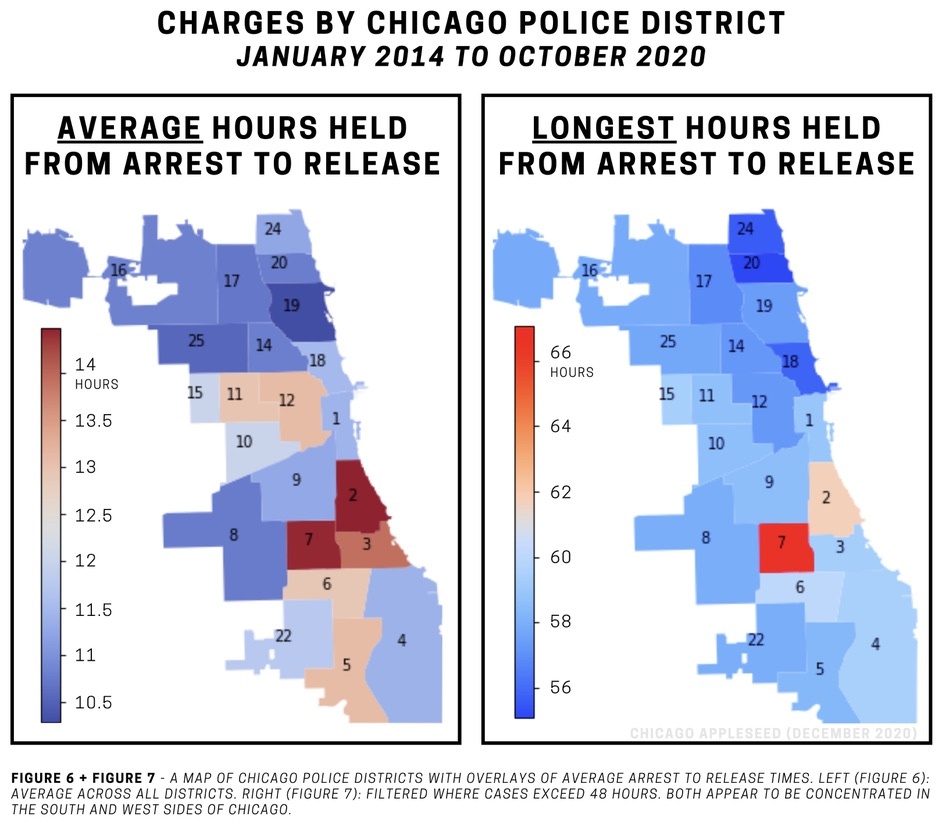

There are more variables to consider when it comes to examining arrests, such as location. To understand if location had an impact on holding times, we analyzed length of stay by police district and a few trends start to appear.

- Longest Holding Times (About 14.5 Hours): District 2 and District 7

- Second Longest Holding Times (About 13 Hours): District 4, District 5, and District 12

- Shortest Holding Times (About 10 Hours): District 25 and District 19

Although arrest data reflect the racial divide already apparent in arrest numbers, the lens of geography puts the data into context. For instance, as provided by a Chicago Reporter interactive map, Chicago communities with the longest arrest holding times (orange and red) seem to overlap with majority Black neighborhoods in Chicago’s West and South Sides. While many factors go into an arrest, for extraordinary cases, the data suggests that the police, race, and location are influential factors while the alleged crimes are minor factors.

CHARGES BY TIME

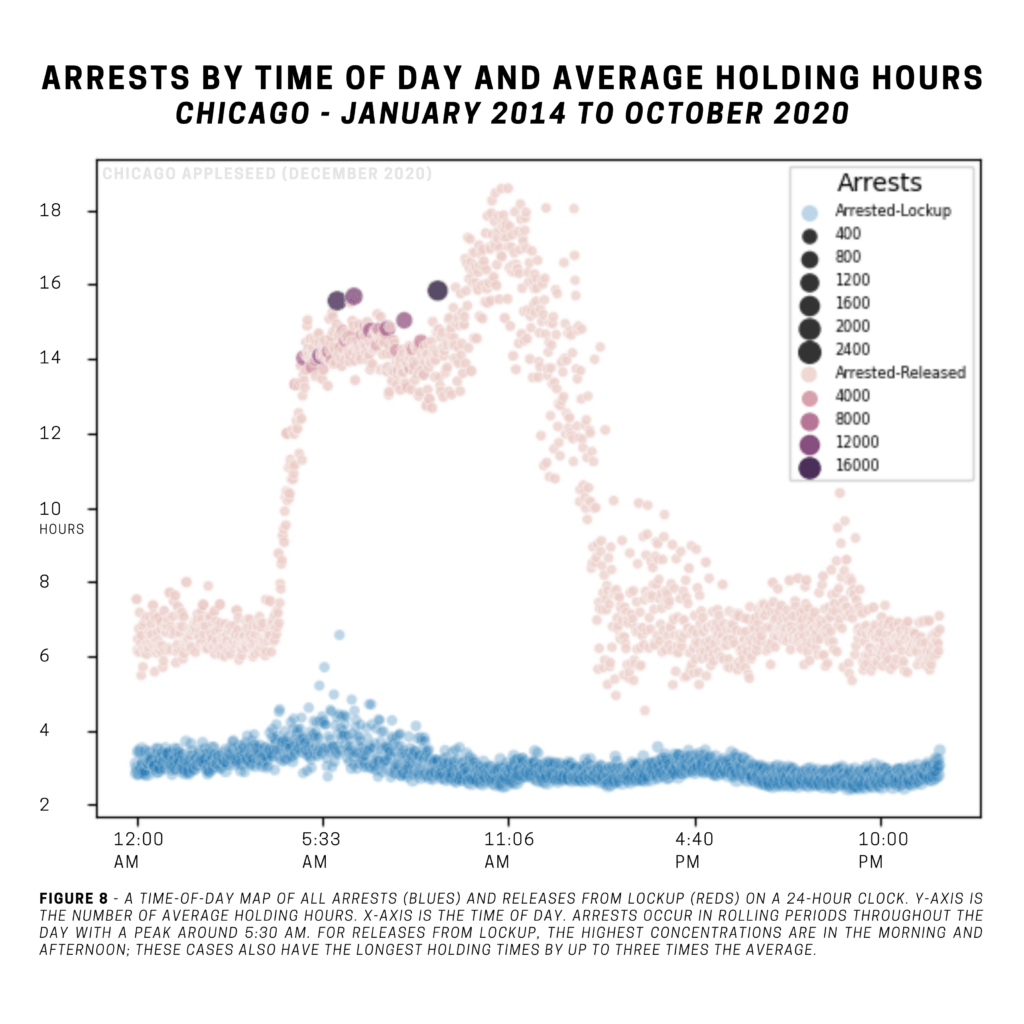

This section explores a unique element of time in the arrest dataset that, to the best of our knowledge, has not been widely available before. Although the utility of this data is not immediately clear for this analysis on holding times, other research efforts may benefit from this type of granular data.

While there are four key datetime stamps available for each of the 536,000 arrest records, we conducted a preliminary time series analysis of the arrest and release times. The other time data not depicted here includes bond date and lockup date.

- Time of Day: In Figure 8, we plotted every record according to the time stamp in a 24-hour period. For each point, larger and darker bubbles represent the times with more arrests [See Figure 8].

- Arrest to Lockup: The series of points in blue represents each arrest by time of day and length of time from arrest to lockup.

- Arrest to Release: The series of points in red hues represents each release by time of day and length of time from arrest to release.

CONCLUSION

The Supreme Court holds that police have a duty to release people as soon as possible but also provides a margin of 48 hours to account for an ineffective system. The 48-hour soft rule may protect some people’s Fourth Amendment rights, but based on the data, it doesn’t appear to go far enough in Chicago. The definition of extraordinary can be completely arbitrary. According to the data, in more than 99% of all cases, Chicago police hold people for less than the threshold; however, there are thousands of other cases that troublingly go for hours — or even days — past 48 hours from the initial point of arrest.

Given the ambiguous nature of “extraordinary circumstances,” we analyzed arrest records to see if patterns in the data reveal something about how police interpret such circumstances. Our initial findings indicate that, for the most part, arrests with holding times in excess of 48 hours are no different than any other arrest. These findings are based on an initial, two-tiered classification of the lead charge in a given arrest. Further, the arrest records for holding times generally reflect the same disparities in race seen throughout the system, suggesting almost no difference in arrest holding times that exceed 48 hours by race. As a result, our initial conclusion is that extraordinary arrests are loosely based on (1) the type of charge, (2) arbitrary, (3) divided along race, or a combination of the three.

Despite the initial conclusion, a geospatial analysis of the same data suggests that both location and race might actually explain differences in holding times. The longest arrest holding times belong to Chicago Police District 2 (Wentworth), District 7 (Englewood), District 4 (South Chicago), District 5 (Calumet), and District 12 (Near West), on Chicago’s West and South Sides. In the absence of other compelling variables, is it possible that race and location have more to do with incommunicado detention than the actual crime?

At this time, this analysis is inconclusive, but we leave you with four points:

- The data herein represents a tremendous opportunity for analysis but is still incomplete because there are data quality issues that require further investigation and scrutiny — further peer review of our analysis is both necessary and welcome.

- Since both the law and data suggest that ‘extraordinary cases’ are either arbitrary or racially divided, there may be an opportunity for civilian oversight on police practices as they relate to arrest holding times.

- At this stage of analysis, it is still not clear what factors are responsible for very long holding times — questions along this topic may inform next steps in research.

- Finally, as we continue to research this dataset and explore relationships to court reform, we are interested in your comments and collaboration.

Justin Chae is a part-time Collaboration For Justice/Appleseed Network Fellow and is a full-time graduate student at Northwestern University studying Artificial Intelligence.

Sarah Staudt has been Senior Policy Analyst and Staff Attorney at Chicago Appleseed since 2018, where she works primarily on criminal justice issues. Before coming to work with Chicago Appleseed, Sarah was an attorney with the Lawndale Christian Legal Center (LCLC) where she focused on juvenile justice matters.

Data Availability & Methodology: https://github.com/justinhchae/appleseed_public_arrests

DISCLAIMER: This site provides applications using data that has been modified for use from its original source, www.cityofchicago.org, the official website of the City of Chicago. The City of Chicago makes no claims as to the content, accuracy, timeliness, or completeness of any of the data provided at this site. The data provided at this site is subject to change at any time. It is understood that the data provided at this site is being used at one’s own risk.