Policy Perspectives: Dr. Shari Diamond on Bond Court

Recently, Chicago Appleseed sat down with Northwestern University Professor of Law and social psychologist Dr. Shari Diamond to discuss her remarkable recent work on courts and juries.

In 2010, Dr. Diamond published a study (pdf) of Cook County Bond Court establishing a causal relationship between videoconference hearings and judges ordering higher bail amounts. She is currently working on a project which gives her unequaled access to observe jury deliberations.

You can read Dr. Diamond’s complete bio here.

Chicago Appleseed: You are part of a growing number of researchers applying empirical practices to the legal field. How does this approach differ from traditional legal research, and why is it important?

Dr. Shari Diamond: Traditional legal research is extremely important. There’s no question that doctrinal analysis gives a sense of what the law is and expects. But many times what you need to know is how the law behaves and how people respond to it. So, the only way to know how the law and legal institutions behave requires a look at actual behavior. We look at the behavior that the law attempts to regulate, the procedures it puts in place, the legal institutions that are supposed to accomplish certain goals–to see whether in fact they do accomplish those goals. It’s almost hard for me with a modern sensibility to imagine any other way of sensibly approaching our assessment of the legal system.

Do you think it’s appropriate for practitioners to take the empirical research to apply directly practice, or is there an intermediate step to be taken? Can you make a direct application of research to policy?

It depends on whether direct application is easily done. Sometimes a researcher will ask a question that isn’t particularly interesting to the policy matter that is on the table. Or it’s only partially relevant, so there’s some extrapolation or adjustment or modification that needs to be done. This is an academic’s answer: it depends.

Has empirical research made it’s way onto policy makers desks?

I think it’s happening more frequently. For example, there has been a movement of late to introduce very small changes in the way trials have been conducted. And that is to give jurors a copy of the written jury instructions. In other words, incremental reforms have been implemented using evidence-based practices, but there are also times when research is ignored.

In 2010, you published an illuminating study of the impact of closed circuit television hearings on Cook County bond amounts. How did you come to work on the study with Locke Bowman and the McArthur Justice Center?

I knew Locke, and he talked to me about the [bond court litigation] that he was involved in. We sat and talked about it, and it became clear that it should be possible to do an evaluation of whether the closed circuit television arrangement had caused any change in bond decisions. That was essentially the lurking empirical question in Locke’s case. Since the bond court change had taken place in 1999 that meant that, if the records were reasonably good, it would be possible to look at behavior before the change, and a long time afterward. It was an ideal situation for making this kind of “interrupted time series” design to see whether the interruption had caused a change.

And what did you conclude?

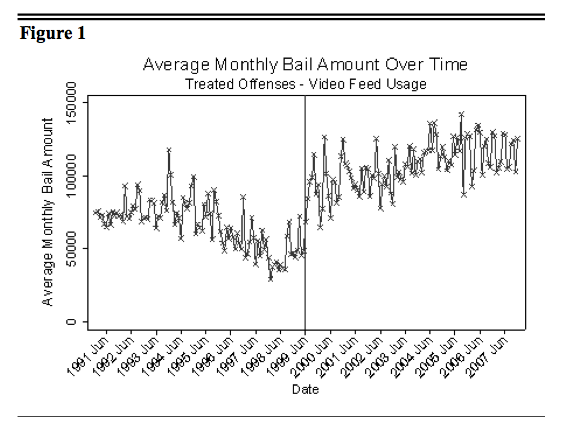

The results were quite dramatic. For those offenses that were affected by the change–that is, those offenses for which a cctv hearing was used after 1999–the amount set for the bond went up substantially. We had a kind of natural control group in offenses for which live in-person hearings continued to be conducted over the same time period. We did not see a change in that group’s bond amounts. So the graphs [see Figure 1 below] kind of popped out to show the change.

What do you think drove that change? The CCTV used in Cook County was the cause, but why did it cause the uptick?

That’s really the question. There were a number of things about the particular set-up for those hearings that were troubling and potentially influential that are not inherent to all cctv hearings. And there were some that are or may be inherent.

In the course of the project, we went down and watch the hearings. I thought it was important that I had a feel for what it actually looked like in place. The cctv they had probably dated back to 1999: tiny screen, black and white, and a lack of contrast that meant it was particularly difficult to see the faces of the defendants who were dark-skinned. That it was difficult to see them.

The set-up also meant that the defendants’ attorneys were in the courtroom, so their representation was kind of split. If they wanted to say something to their attorney during the hearing, they had no way of doing that. So their representation opportunities were impaired under that arrangement. Overcoming that without an in-person hearing would be difficult to accomplish.

Do you have any thoughts on what might have impacted the judges’s decision-making?

Honestly, we just don’t know. This is where there’s an imperfect match between the existing research and the study we did. There is some may be evidence that people may behave differently in response to live and in-person versus video presentations, but we certainly don’t know if that affected the judges in this situation. It was certainly easier for the judges to pay less attention to the particular defendant in the set-up that existed in Cook County than if the defendant had been standing in front of them., but whether you could say that that attention would’ve been different from the live hearing.

There’s been a lot of discussion lately in the public sphere in the newspaper–CCBP President has really taken up the mantle of bond court reform. Do you have any thoughts on changes that you think could be simple or incremental to make to the bond court system?

One of the disadvantages judges have in making these decisions is the limited amount of information they have. The question is whether you can increase that amount of information efficiently, and whether it would affect decision-making. As you know, bond hearings are generally very brief and court typically results in very little time spent per defendant. That usually means that they use very little information is presented. And it may be that judges spend so little time because they simply don’t have much information to inform their decisions.

I have to say that on the day that I watched, it appeared–and we have no records on this so we couldn’t test it directly–that there was substantially more time spent with defendants represented by private attorneys than those represented by public defenders. The vast majority of defendants are represented by public defenders. Whether that impacted the decisions that were made, I have no data on that.

I understand you’re currently working on a book about juries which includes analysis of recorded jury deliberations. That sounds fascinating. Could you give us a preview of that work?

That project, which has been going on for some time and is reaching fruition (we’ve published a fair number of articles but the book is in process) is on civil juries. I was ecstatic at the opportunity and it’s not something I expect to come again. I refer to it as my “Camelot” project.

There were some judges in Arizona who decided that in the course of evaluating a jury reform that they were implementing that it would be good to know how juries were responding. So they let us do an experiment in which some juries were told that they could discuss the case during the breaks of the trial, and others were told that they could not. And we were allowed to videotape the juries during their breaks in the course of the trial as well as all of their deliberations in order to study their behavior.

Can you share any interesting findings so far?

The juries work very hard to get the right answer. Their definition of the “right answer” may not completely jibe with every dot and jot of the law, but in large measure it’s quite consistent with it. I think that the way they correct each other and put together information has made it clearer to me than it ever was how valuable it is to have the group as a decision maker. Jurors bring a lot of personal experience and different amounts of attention to specifics in the evidence to bear as they talk about the evidence.

And do they discuss damages awards? Anything interesting come out of that?

These are very complicated judgements that we ask them to make and the jurors have to work hard, with surprisingly little guidance on how they should go about making them. A couple of overriding themes emerge: 1) Jurors are very skeptical about claims for damages. So they scrutinize them very closely looking for “the greedy plaintiff” or the claimed injury that might not actually be there, or the extra doctor visits that aren’t warranted. Particularly in the low-impact ordinary personal injury cases.

Second, they also struggle in understandable ways to arrive at appropriate future damages. For example, one juror commented that it would be helpful to have a crystal ball. Future damages in an odd sort of way requires them to have a crystal ball. Because this is the one time when an award may be made, and if the claim is that the injury lasts a lifetime and further medical treatment may be needed, the jurors have to predict what the future will hold. Then they have to make that decision.

What the jury deliberations reveal overall is that jurors pool their different experiences and bring considerable care and effort to a challenging task.

We’re interested in how to bring more humanity and efficiency to the criminal justice processing system. Why do you think it’s important that that stage in the process be more fair and yet efficient?

Well, I wonder–and this is pure speculation–whether there wouldn’t be a potential triage system that could be established in reaching bond decisions. We know that, for example, somebody who has no prior record and is being charged with a particular kind of offense is typically given a recognizance bond. Perhaps we could do what hospitals do in emergency rooms and triage people out, so as to and leave more attention for the more difficult and questionable kinds of cases. I don’t know enough to be able to set that up, but it does seem to not make sense to treat all the cases the same in this situation. Which is what it looks like we do, except for those represented by private attorneys.

Could you use actuarial or statistical models to make these decisions?

Absolutely, but I’m arguing for a more mixed model sort of approach. People resist when you get some kind of bad decision made for you based upon actuarial tables, even though they can in fact be more equitable if the criteria you include are legally legitimate. But if you were to say, okay, there are two pots here: one says you will get a complete hearing, and one says, we don’t even have to put you through that process (because you are clearly eligible for release on recognizance). Then, you’re really not penalizing those in the first pot. You’re just saying, we have to look at this more closely.

There’s an interesting challenge with relying upon statistical predictions within the criminal justice system, which is the issue of prosecutorial and judicial discretion. But their caseloads are massive. Do you know where policy has balanced those issues?

The classic example is the federal sentencing guidelines. They were originally constructed as primarily based upon a summary of what had happened in patterns of sentencing before, to regularize them, and then adjust them from a normative standard of what was thought should be done. So, it was a mixture.

I was a strong advocate of sentencing guidelines before the federal guidelines went into effect. But what happened was a ratcheting up in the setting of those guidelines over time. The public argument always seemed to be in favor of greater severity: oh, yes, we’re going to really punish these things. So, until fairly recently judges felt completely bound by those guidelines. The guidelines replaced discretion with harshness rather than replacing discretion with regularity and rationality.

That’s the balance between the values of discretion and the equal treatment of a non-discretionary system. That’s a constant tension.