Examining “Cook County E-Court” and Looking Toward the Future of the COVID-19 Pandemic

Written by Sarah Bloomquist and Allison Leon

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, criminal courtrooms in Cook County were shuttered for all but limited proceedings beginning March 13, 2020, with judges allowed to hear only bond and preliminary hearings, arraignments, and guilty pleas. This policy has resulted in delays for litigants, including – importantly – those who are detained awaiting trial, and risks creating a serious ballooning of the criminal docket.

In several jurisdictions in Illinois and around the country, courts have utilized videoconferencing platforms (notably Zoom), to hold substantive legal proceedings without risking the physical health of litigants, witnesses, judges, lawyers, or courthouse staff; on May 4, 2020, Cook County outlined procedures for Zoom plea hearings. While beneficial from a public health standpoint, remote court proceedings carry new implications for people’s rights and practical functioning of a court proceeding.

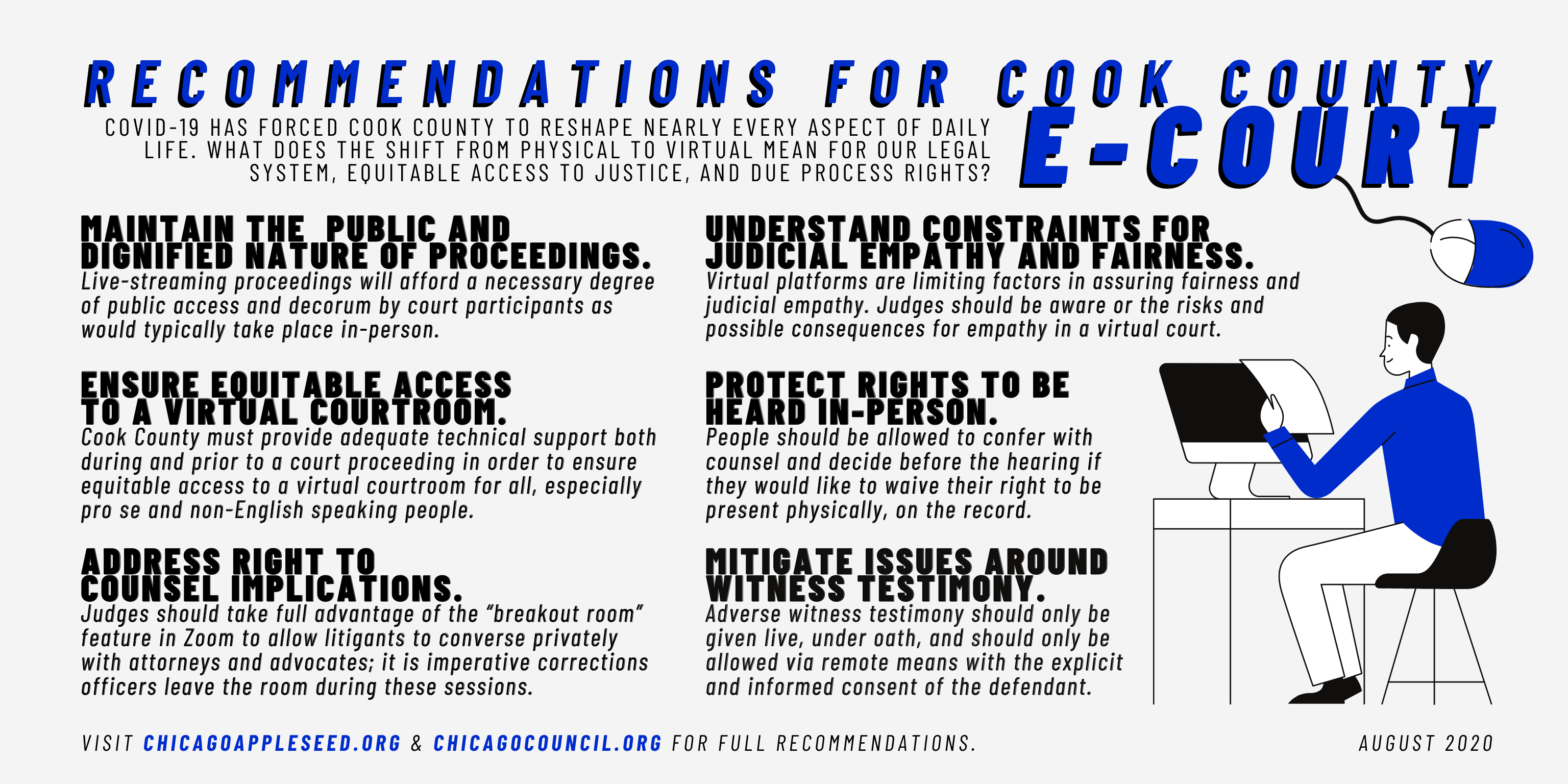

As highlighted in our full report, virtual court in Cook County introduces new obstacles to people’s due process and access to counsel rights. In our “Cook County E-Court” report, Chicago Appleseed and the Chicago Council of Lawyers make recommendations to address several of these equity, ethics, and constitutional issues.

- Our “Cook County E-Court” report introduces obstacles to the defendant’s right to confront witnesses. Virtual court makes testimony it practically challenging and constitutionally questionable, because the Confrontation Clause fails to prevent defendants from calling non-hostile witnesses via phone or videoconferencing.

- Virtual court proceedings via videoconferencing threaten a person’s right to confer with counsel before and during trial. A case study of videoconferencing in Chicago immigrant removal hearings by Chicago Appleseed and Legal Aid Chicago (formerly LAF) found that “videoconferencing creates a major barrier to a detained immigrant’s access to counsel,” primarily causing issues with the ability of detained people to confer with their representation.

- There are also ethical concerns related to a person’s right to be physically present for court proceedings. While it is not an express right to be heard in person, the right to be present is implied from the due process clause of the Constitution. Case law in Illinois has established that virtual participation by a defendant is permissible, absent a showing on the record that the lack of physical presence affected the defendant’s constitutional rights.

- Remote proceedings also pose the threat of a possible deficiency in empathy from judges, when a defendant is a picture on a screen rather than a physical human presence. Surveys of UK legal practitioners found that “70% of respondents said it was difficult to recognize whether someone who was on video had a disability” and that “defendants appear disengaged and remote . . . they often give a nonchalant, poor account of themselves and we are left to infer that they couldn’t care less that they are disrespectful of the court.” Another U.K. study found “increased rates of custodial sentences compared to non-Virtual Courts.”

- E-Court also introduces an ethical limbo in regard to the necessity of public access to the courtroom, an-person screenings of virtual court threaten people’s health and general broadcasting of courtroom proceedings dually threatens what anonymity respondents may have had in the context of normal, physical court.

- The socioeconomic implications of virtual courts are blatantly clear and must be reconciled with. Virtual proceedings by their very nature exacerbate existing inequality, especially for pro se litigants and people with limited access to high speed internet, unfamiliarity with technology, or language barriers.

There are several ways to maintain equitably and constitutionally-sound proceedings while allowing Cook County Court via remote means. Our report offers practical policy recommendations to help mitigate witness testimony issues, address implications with right to counsel, understand constraints for judicial empathy, protect a defendant’s right to be heard in person, maintain the public and dignified nature of proceedings, and ensure equitable access to a virtual courtroom.

Among the recommendations we provide, our “Cook County E-Court” report examines technological solutions to permit respondents to communicate confidentially with counsel during and before proceedings; discusses a range of participant control platforms that allow the public to observe court virtually; and explains the importance taking special care to ensure that notice and support is given effectively to all litigants—especially pro se and non-English speaking people.

The Collaboration for Justice of Chicago Appleseed and the Chicago Council of Lawyers would like to thank the pro bono teams at Latham & Watkins for preparing this report, and Loeb & Loeb and Harrison & Held for the research support.