One-Hour Access to Counsel in Police Stationhouses: A Cost-Saving Necessity

By Elijah Gelman, Chicago Appleseed Undergraduate Intern

In January, Chicago Appleseed Senior Policy Analyst Sarah Staudt discussed the importance of newly proposed legislation cementing the right to counsel for every person arrested in Illinois within one-hour of arrest. Despite it being necessary to both ensure arrested people’s access to their right to counsel and to reduce Cook County’s exorbitant false confession rate, the legislation has stalled. With this essential legislation now up in the air, it is important to recognize that CPD’s denial of counsel to arrestees is not only a grave injustice, but creates major, unnecessary costs to taxpayers.

CPD’s denial of counsel to arrestees is not only a grave injustice, but creates major, unnecessary costs to taxpayers.

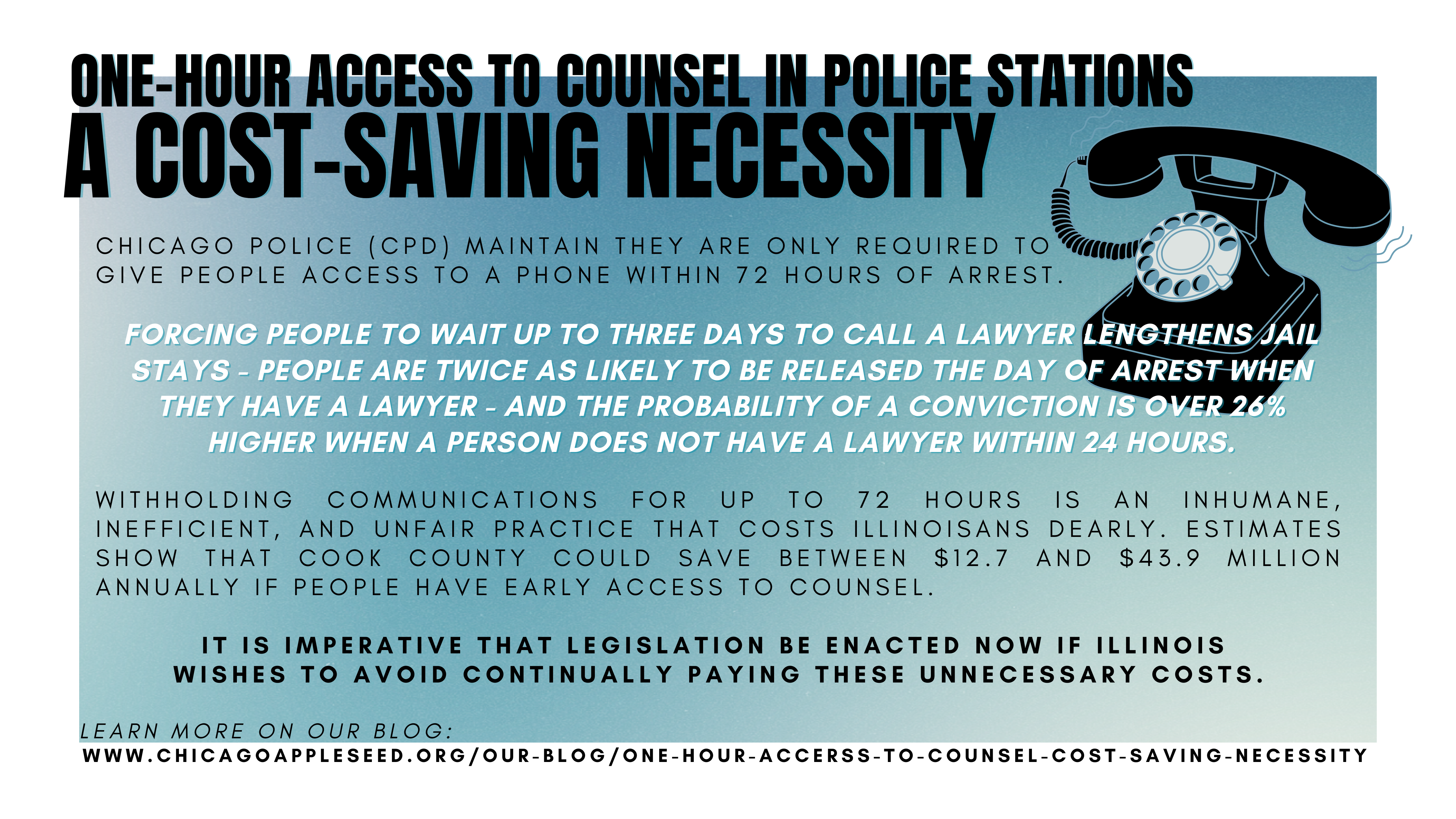

The costs begin with unnecessarily long jail stays. The Chicago Police Department (CPD) currently maintains that it is only required to give people they have arrested the ability to phone for counsel within 72 hours of arrest. Forcing people to wait up to three days to access counsel lengthens their jail stays, as studies show people are twice as likely to be released the day of arrest when they have a lawyer.(1) Early access to counsel gives defense attorneys more time to assess their clients’ cases and find relevant information that can get them out of jail.

The savings from reduced jail stays would be significant. A 2015 study sought to calculate how much Cook County would save if people were given access to counsel within 24 hours of being arrested. It found stark differences in the length of jail stays between those who were given prompt access to counsel and those who were not. Arrested people denied early access to counsel spent on average 132 days in jail if convicted and 151 days in jail if not convicted.(2) In contrast, people given early access to counsel spent on average 114 days in jail if convicted and a mere 10 days in jail if not convicted.(2) This means that those who obtained access to counsel within 24 hours of arrest spent on average 18 fewer days in jail if convicted and 141 fewer days in jail if not convicted. Jail stays are further reduced when one considers the effect early access to counsel has on conviction rates, as the study notes that “the probability of a conviction…declines by 26.7[%]” when an arrested person “has a lawyer within [24] hours.”(2) When the reduced jail stays and lower conviction rate are applied to the average daily population of Cook County jails, Cook County would “save between $12.7 and $43.9 million annually” from reduced jail stays alone if arrestees have early access to counsel.

More pretrial time for defense attorneys with their clients has further financial benefits, including an increased likelihood that people will avoid excessive sentences. A study from the Justice Policy Institute shows that if defense attorneys had more time with their clients, they would be better equipped to “secure accurate and appropriate sentences” that could save “taxpayers tens of millions of dollars a year.” More “appropriate sentences,” for example, may take the form of diversion programs, which have been shown to be “cheaper and more effective at reducing recidivism than incarceration.” The most effective time for lawyer intervention is often at the beginning of the case, when crucial decisions about whether a person will or will not be in jail pretrial are made. Investigation by defense lawyers within the first few days after an arrest can also be crucial; many forms of evidence, most importantly surveillance video, are automatically deleted after a relatively short time period unless a request for preservation is made. Representation early in the case can alert lawyers that this kind of evidence may exist, and can make the difference between crucial evidence being preserved or destroyed.

Overall, more effective representation leads to better case outcomes and fewer sentences of incarceration. The downstream consequence is that effective representation likely helps avoid recidivism down the line. Reducing recidivism comes with its own savings. The Illinois Sentencing Policy Advisory Council found that Illinois taxpayers pay, on average, $50,835 each time recidivism occurs, and expects recidivism to “cost Illinois over $13 billion” by 2023.

Illinois’ greatest source of savings from ensuring prompt access to counsel may be the reduction of police misconduct—especially in Chicago. Early access to legal counsel can deter police misconduct, as officers are less likely to break laws if they know defense attorneys will have the ability to “gather evidence…and assess claims of brutality within twenty-four hours of arrest.”(2) This deterrence is essential for Illinois. Racist police misconduct and corruption has historically and continues to plague Chicago and cost Illinois taxpayers. According to NPR, Chicago has paid over $500,000,000—half of one-billion dollars—for police misconduct in the past ten years; an investigation by the Better Government Association found that two-thirds of wrongful convictions are attributable to “police misconduct or error” that have cost Illinois taxpayers at least $253 million since 1989. There is no sign that these payments are slowing down, either, as Illinois City paid $11 million in a wrongful conviction settlement just this March.

Illinois’ greatest source of savings from ensuring prompt access to counsel may be the reduction of police misconduct—especially in Chicago.

Over $100 million of Chicago’s police misconduct costs can be attributed to “settlements, reparations fees, and legal defense” for former Chicago Police Commander John Burge. From 1972 to 1991, Burge led his Chicago police force to commit numerous acts of torture, 118 of which are currently documented. Burge tortured “mostly black suspects” in a variety of ways, including “mock executions through Russian roulette, sticking a gun in a suspect’s mouth, and the use of a cattle prod.” While Burge’s tortuous reign is over, Chicago’s issues with police misconduct are not, as evidenced by the continual payment of misconduct settlements. However expensive, the real costs of police misconduct are the intergenerational traumas being perpetuated on our city’s primarily Black, Brown, and poor communities by unacceptable police practices.

It should not be assumed that this list of current costs and potential savings is in any way comprehensive. Access to legal counsel within one-hour has a plethora of unquantifiable benefits, as well. By reducing jail stays and wrongful convictions, people can avoid job losses due to absence from work, an erroneous “criminal record” that diminishes their “wages, employment rates, and yearly earnings,” and many other unnecessary collateral consequences of pretrial detention.(2) While these savings may be difficult to measure, it is undeniable that the Illinois economy would gain much if all Illinoisans had higher and more stable incomes.(2) Considering that Illinois wrongful convictions led to the imprisonment of innocent people for a collective 926 years between 1989-2010, it is likely that these unquantifiable savings are quite large.

Withholding communications for up to 72 hours after arrest is an inhumane, inefficient, and unfair practice in the Illinois criminal legal system that costs Illinoisans dearly. The human toll these policies take is incalculable, but they cost the City millions that could be better spent on the needs of our communities. It is imperative that legislation be enacted now if Illinois wishes to avoid continually paying these unnecessary costs.

To learn more, view our information sheet or visit the websites of First Defense Legal Aid and the Cook County Public Defender.

ADDITIONAL REFERENCES

(1) Colbert, Douglas L., et al. “Do Attorneys Really Matter? The Empirical and Legal Case for the Right of Counsel at Bail.” Cardozo Law Review, vol. 23, 2002, pp. 1719–1793. HeinOnline, (1755).

(2) Sykes, Bryan L., et al. “The Fiscal Savings of Accessing the Right to Legal Counsel Within Twenty-Four Hours of Arrest: Chicago and Cook County, 2013.” UC Irvine Law Review, vol. 5, no. 813, 2015, pp. 813–841., (828).