Which states protect your right to communicate after arrest?

The Governor signed the Safety Accountability Fairness and Equity – Today (SAFE-T) Act in February of 2021. Among the many police and criminal legal system provisions in the law, the SAFE-T Act (IL PA 101-0652) solidifies the right to communicate for all people arrested in Illinois.

In this context, the “Right to Communicate” refers to people’s statutorily enforced right to communicate with the outside world upon being arrested or detained by law enforcement. Without the ability to contact friends, family, or access legal representation at the time of arrest, people may not fully understand or have the ability to safely invoke their Fifth or Sixth Amendment rights. This is particularly an issue in Chicago, where the police department has a history of coercing confessions. Chicago Appleseed’s own research — based on a dataset of approximately 536,000 Chicago Police Department (CPD) arrest records covering 2014 to 2020 — found at least 6,282 cases of people held by CPD for longer than 10 hours, for a maximum of 2 days, between the time of first detainment and official booking; 3,103 of those cases were of people held longer than 48 hours, for a maximum of 4 days from initial arrest to release.

With the provisions of the SAFE-T Act, Illinois is now one of only a handful of states in the US with explicit protected access to communication rights for people in police custody.

Before the SAFE-T Act, people arrested in Illinois were given the “right to communicate with an attorney of their choice and a member of their family by making a reasonable number of telephone calls…within a reasonable time after arrival at the first place of custody.” Unfortunately, law enforcement often interpreted the word “reasonable” in an unreasonable way — and made people wait as long as 72 hours to access a phone. Now, effective in 2022, all law enforcement officials in Illinois will be required to provide people they have arrested with the ability to make three phone calls within three hours of arriving at a detention facility (the time starts over at a new facility) and give people the ability to retrieve phone numbers saved on their cellphones. Likewise, law enforcement are required to display the phone numbers for police station representation units (PSRU) of local Public Defenders’ Offices, if applicable, like in Cook County.

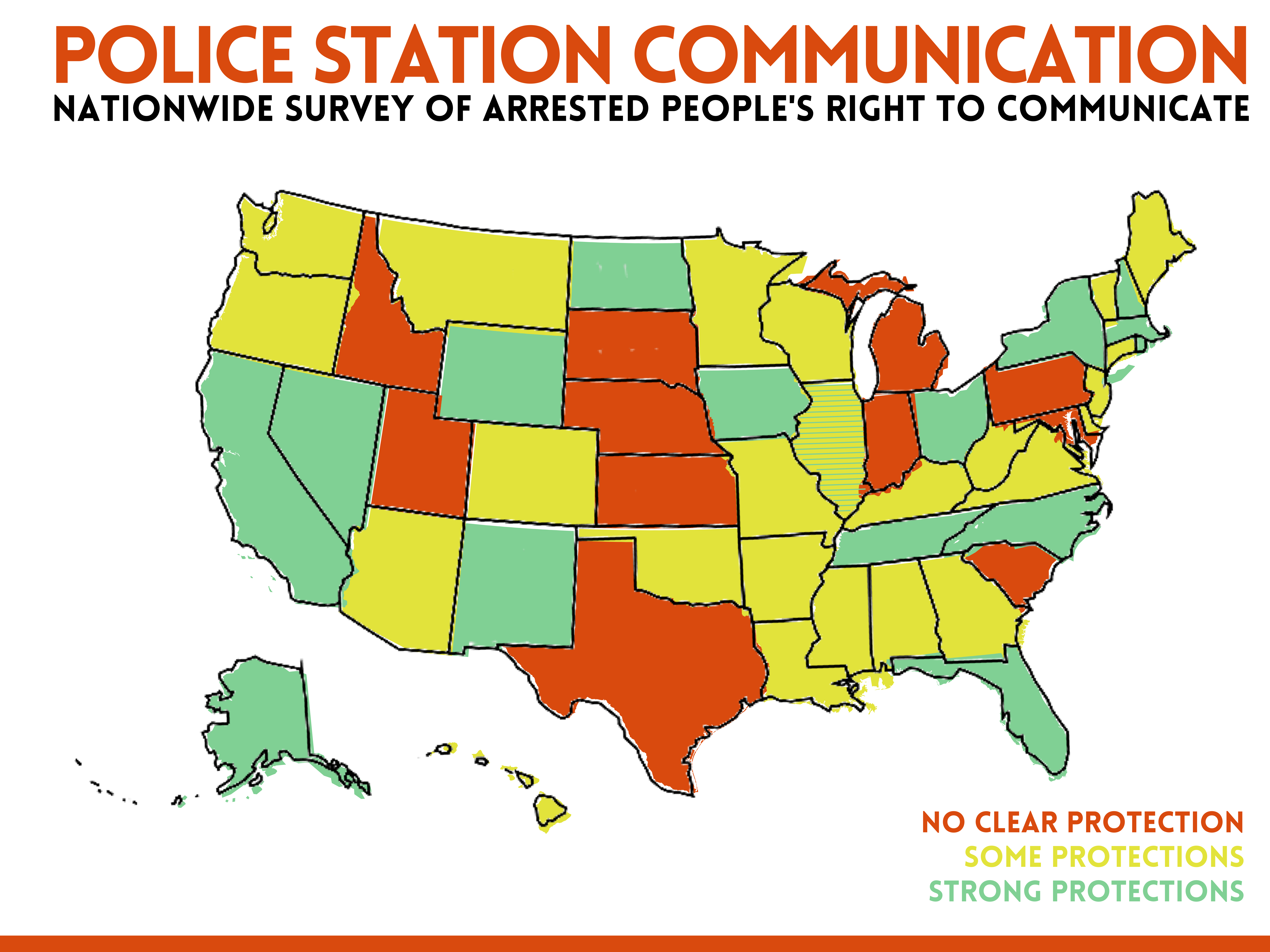

Chicago Appleseed conducted a nationwide analysis of the right to communicate in each US state based on the combination of each states’ statutes, case law, informal programs, and statements from regional attorneys.

We categorized the fifty states’ rights to communicate into three categories (no clear protection, moderate protections, and strong protections) by looking at seven key areas of difference:

- Timeframe: Does statute mandate the time allotted to arresting officers before they are required to provide the arrested person with the opportunity to make a phone call? When does it begin?

- Number of Calls: Does statute mandate a specific number of calls people can make, if any, or do vague terms guide the number of calls allowed?

- Recipient: Can people contact a family member or friend, or does the law limit contact to an attorney? Can purposes for contacting someone exceed the securing of council?

- Expense: Are both local and long-distance phone calls provided free of charge?

- Privacy: The general rule is that attorney-client conversations are subject to privilege, but if the accused is speaking to anyone other than an attorney, can law enforcement listen to and use these phone conversations as evidence? Does statute support attorney-client privilege in phone discussions?

- Penalties: Does the state define a penalty for officers who refuse or fail to provide people’s rights to communicate?

- Qualifiers: Do all arrested people have the same rights to communicate, or is the eligibility of this right based on the nature of the allegation? Generally, states that restrict the right based on allegation do so for people accused of drunk driving or domestic violence.

Based on these factors, Chicago Appleseed found that about 46% of states provide “moderate protections” for their residents, 22% of states have “no clear protections,” and only 32% — 16 states — provide “strong protections” for arrested people’s rights to communicate.

STRONG PROTECTIONS

Sixteen states have particularly strong rights to communication — either in statute or case law: Illinois (once the SAFE-T Act goes into effect in 2022), Alaska, California, Colorado, Florida, Iowa, Massachusetts, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Rhode Island, and Tennessee. This category represents jurisdictions whose statutes specify items such as definite or immediate time frames for calls, or makes specifications about the number or allowance of multiple calls.

Some states have notably strong protections. For instance, California stipulates extra calls to arrange for childcare when the arrestee is the primary caretaker of a child and, like Illinois, requires the rights of arrested people to be clearly posted in printed signs at the police station. Colorado is similar to Illinois in that it renews the arrested person’s rights to a phone call if they transfer facilities. In Nevada, people’s “reasonable” number phone calls explicitly include complete calls, rather than just attempts, and in North Carolina, the responsibility of providing a phone call is explicitly put on the arresting officer.

MODERATE PROTECTIONS

The right to communicate for arrested people is generally accepted in many states, but it is difficult to find statutes or case law which define that right, or if the right is defined, the terms of that statute are overly vague — such as was true with Illinois before the SAFE-T Act. These 23 states are Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Hawaii, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, New Jersey, Oklahoma, Oregon, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

NO PROTECTION

Eleven states were either identified by local attorneys and organizations as jurisdictions where the right to a phone call is not afforded to arrestees or there was no mention in case law, statute, or informally: Idaho; Indiana; Kansas; Maryland; Michigan; Nebraska; Pennsylvania; South Carolina; South Dakota; Texas; and Utah.

Click here for Chicago Appleseed’s full report, “Nationwide Jurisdictional Comparison of the Right to Communicate After Arrest.” More information on the SAFE-T Act and people’s right to communicate can be found on our Community Resource page.

Contributors: Mercedes Molina is a rising 2L and the Robina Public Interest Scholar at the University of Minnesota Law School and a Public Interest Law Initiative (PILI) Intern, Dane Christensen is a recent dual-graduate of the University of Chicago’s Law School and Booth School of Business and Public Interest Law Initiative (PILI) Fellow, and Stephanie Agnew is Chicago Appleseed’s Pro Bono & Communications Coordinator.