REPORT: “Solutions rather than Obstacles” – An evaluation of the Hearing Officer Program in Cook County’s Domestic Relations Court

Every year, the Domestic Relations (DR) Division of the Circuit Court of Cook County processes approximately 40,000 divorce and child support cases. Because DR cases are handled in civil court, neither individual party — the petitioner nor respondent — have any right to free or accessible legal representation. Legal Services Corporation reported in 2017 that for 86% of the civil legal issues of low-income Americans, those litigants receive inadequate or no legal help. According to the Illinois State Bar Association, in 2015, at least 91% of the 102 counties in Illinois reported that more than 50% of civil cases in that jurisdiction involved a self-represented litigant on at least one side. According to the Institute for the Advancement of the American Legal System, 75% of self-represented litigants expressed that they would have preferred to work with an attorney.

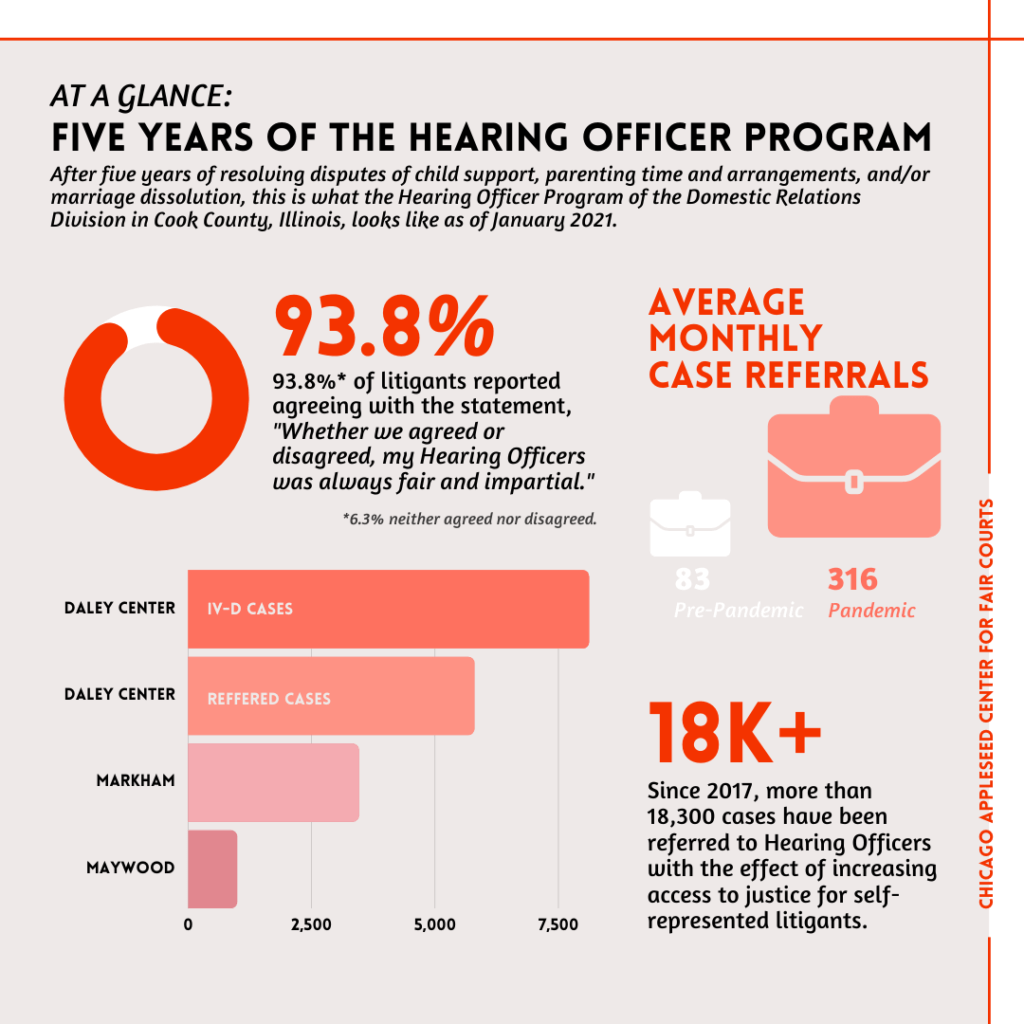

To address some of the inequities facing self-represented litigants in family court, Cook County introduced the Hearing Officer Program in 2017. The program is county-funded and utilizes administrative law judges in domestic relations cases to offer support for individuals who cannot afford to secure representation for any number of reasons. The program operates in Chicago’s Daley Center and in the Markham and Maywood Courthouse. Both Markham and Maywood are locations with large populations of people of color and large populations of low-income individuals: in Markham, 79.1% of residents are Black or African American, 9.9% are Latinx, and less than 10.4% are white, Asian, two or more races, or Indigenous North American, Hawaiian, or other Pacific Islander; in Maywood, 68.6% or residents are Black, 26.9% are Latinx, and less than 5% are white, Asian, or Native.

Chicago Appleseed Center for Fair Courts was involved in planning the Hearing Officer Program, and from February to June 2021, we systematically evaluated the efficacy of the Hearing Officer Program in year four of its operation. Our new report, “Solutions rather than Obstacles”, examines the data to understand where disparities in representation and access may still exist and offers potential avenues for improvement in the future. Our findings show that the Hearing Officer Program serves a population that is very often low-income and, according to one interviewee, are “predominantly Black.”

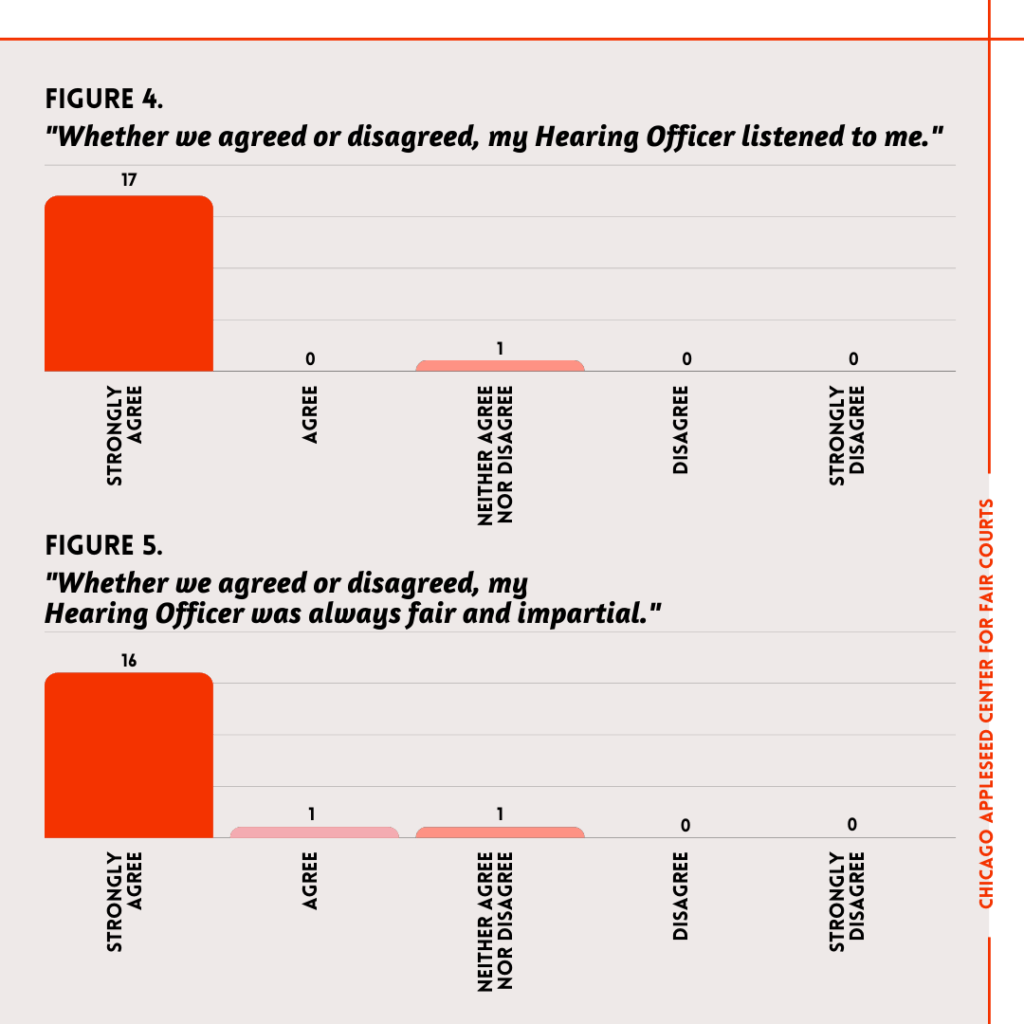

Our evaluation involved the interviewing of key stakeholders in the Hearing Officer Program, including judges, lawyers, Hearing Officers, and self-represented litigants, and analyzing data provided by the Presiding Judge of the Domestic Relations Division. The interviews were composed of open-ended questions where participants were asked about their involvement with the program, their perspectives on how the program works, and what could be done to further improve the program, and the self-represented litigant survey asked about personal experiences — focusing on whether or not the Hearing Officers were helpful, fair, and respectful. Overwhelmingly, the responses were positive. Judges reported that Hearing Officers aid tremendously in the day-to-day administration of their activities and Hearing Officers move cases involving self-represented litigants through the courts more effectively and efficiently. Litigants overwhelmingly reported that their experiences with the Hearing Officers were positive: that, regardless of the outcome of their case, the Hearing Officer they worked with was helpful (providing aid and solutions to questions and procedural difficulties), fair, and listened to the litigants.

By aiding in the process of moving cases through the courts, Hearing Officers appear to help provide quicker resolutions than judges to matters involving child support, parenting time, and dissolution of marriage, and cut down on time people are forced to spend in court, the costs of getting to court (including transit and parking), and associated expenses with additional time in court (childcare, time off work). Quicker resolutions can have a substantial impact on families: resolving child support calculations makes a material difference in the resources available for childcare and expenses, and resolving questions of parenting time and the dissolution of marriage can resolve ambiguity in the day-to-day functioning of the family. Furthermore, Hearing Officers provide the integral function of allowing litigants who are unable to access professional legal representation to be accurately heard by the court and to feel more comfortable in resolving their legal issues. Hearing Officers are able to spend more time with people, making sure that they are responding to each individual’s specific needs. Hearing Officers create conditions whereby a person’s ability to organize their family according to their needs and preferences is not contingent on their ability to pay for representation.

Broadly speaking, the Hearing Officer Program delivers value to the court system by (1) allowing judges to spend needed time on more complex cases; and (2) providing self-represented litigants with better opportunities to understand, participate in, and quickly resolve their cases. The Hearing Officer Program here supports a definable population (self-represented litigants dealing with child support, parentage, divorce, or other family-related issues) while also alleviating a set of problems within the courts (the lack of judicial time prevents some cases from getting the attention needed to be fully heard). More simply, it would appear the Hearing Officer Program enables the court system to resolve more cases more quickly with greater litigant satisfaction.

Our report offers some suggestions for further evaluation and expansion of the Hearing Officer program. Because we conclude that the Hearing Officer program is working well and providing effective solutions for inequities in the Domestic Relations court, we recommend the expansion of the program. There is no reason to assume that jurisdictions outside of Cook County or other divisions of the Cook County Courts would not also benefit from implementing Hearing Officer Programs. In addition to expansion, the program can be further supported through additional evaluation, expanded collection of demographic and case timeline data, and community education. Importantly, we strongly recommend that the Circuit Court of Cook County establish a broader data collection and reporting system that collects information on demographics and case status, number of continuances, and total time from filing to disposition for all the cases eligible (i.e., those cases managed by the Domestic Relations Division that could be seen by the program) and actually seen by the Hearing Officer Program, as well as contextual measures in relation to operating budget, judges, Hearing Officers, and cases.

Similarly, we suggest that the Domestic Relations Division should consider a re-evaluation of Hearing Officer Program’s goals that better define success and identify specific measures that demonstrate whether the goals are met. The Hearing Officer Program currently captures several types of metrics about program utilization, but using frameworks such as key performance indicators, measures of effectiveness, or measures of performance could help support further evaluation of related goals. Through this and other evaluative reports, Chicago Appleseed has demonstrated the utility of prioritizing litigant satisfaction, so the Court should also further implement formalized measures of satisfaction from litigants, their families, and also from judges and others impacted by the program.

In conclusion, the Hearing Officer Program of the Domestic Relations Division of the Cook County Circuit Court improves access to justice by working on an individualized basis with self-represented litigants to make court processes more navigable and comfortable. The program decreases workload burdens for judges and makes the process itself smoother for both judges and litigants. From this evaluation, it appears as though the program is meeting its goals in making the courts more equitable for everyone, particularly self-represented litigants, so that the ability to navigate the family courts and obtain a viable outcome is not tied to a litigant’s ability to pay for counsel.

Contributors: The Hearing Officer report was researched and written by Kaitlyn Filip, JD-PhD Candidate at Northwestern University & Collaboration for Justice Fellow and edited and prepared by Grace Mueller and Stephanie Agnew on behalf of Chicago Appleseed Center for Fair Courts.