Slowly Returning to Normal: A Look at the Cook County Court Case Backlog in Autumn 2021

As we have reported before, the Cook County Felony Courts saw a massive slowdown in case resolutions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Because in-person courts were closed for the majority of 2020 and some of 2021, trials became extremely rare. At the same time, other kinds of case dispositions, like guilty pleas and case dismissals, also slowed to a crawl. Over time, this created a massive case backlog, with thousands of accused people waiting extended periods of time for their cases to be resolved.

This crisis took on an even more urgent tone in June, when the Illinois Supreme Court Announced that speedy trial rights would be reinstated on October 1. During the pandemic, accused people had been denied their constitutional and statutory right to demand a quick resolution of their case (within 120-160 days). This suspension of constitutional rights helped enable the slowdown of Cook County’s courts; without the pressure of accused people’s demands for trial to force case resolutions, relatively few cases resolved at all.

Now, it seems that the courts are on the right path to successfully rebound from the court backlog and return to resolving cases in a timely manner. We examined the most recently released State’s Attorney’s data on felony cases, which included cases initiated or disposed of through September of 2021.

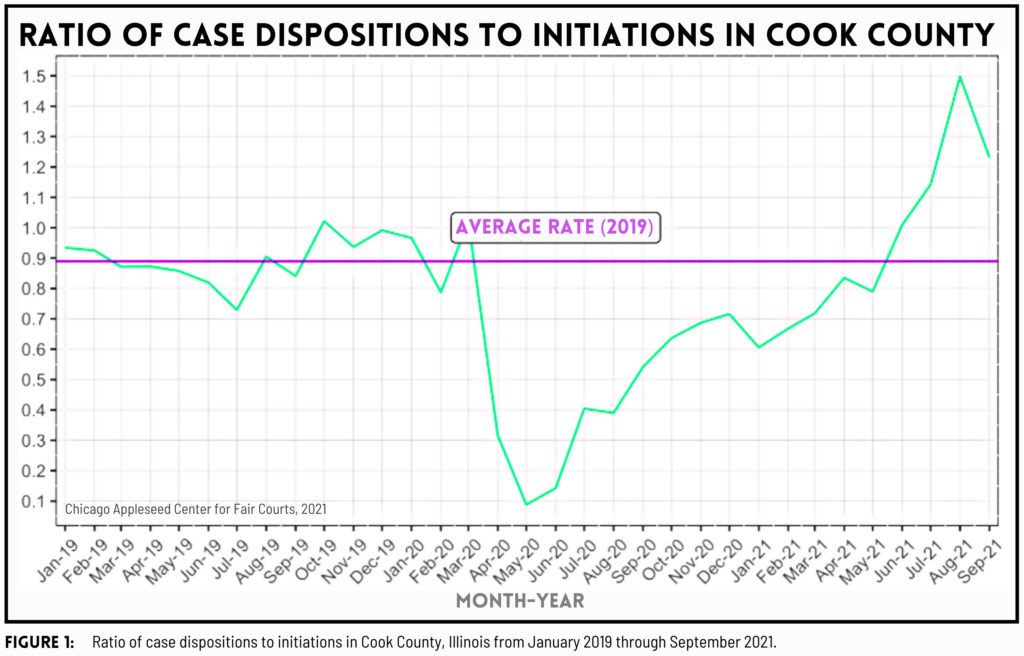

As Figure 1 shows, Cook County normally resolves about 9 cases for every 10 that are initiated each month. During all of 2020 and much of 2021, that rate fell substantially. But the courts were able to rebound to a rate substantially above the normal case resolution rate, resolving 15 cases for every 10 that were initiated in August of 2021. This was vital to recovering from the court backlog. It was not enough to simply return to normal rates of resolutions; the courts needed to work faster than normal in order to both keep up with incoming cases and clear the backlog of cases created during the pandemic. Fortunately, these most recent numbers suggest that the Court is doing that successfully.

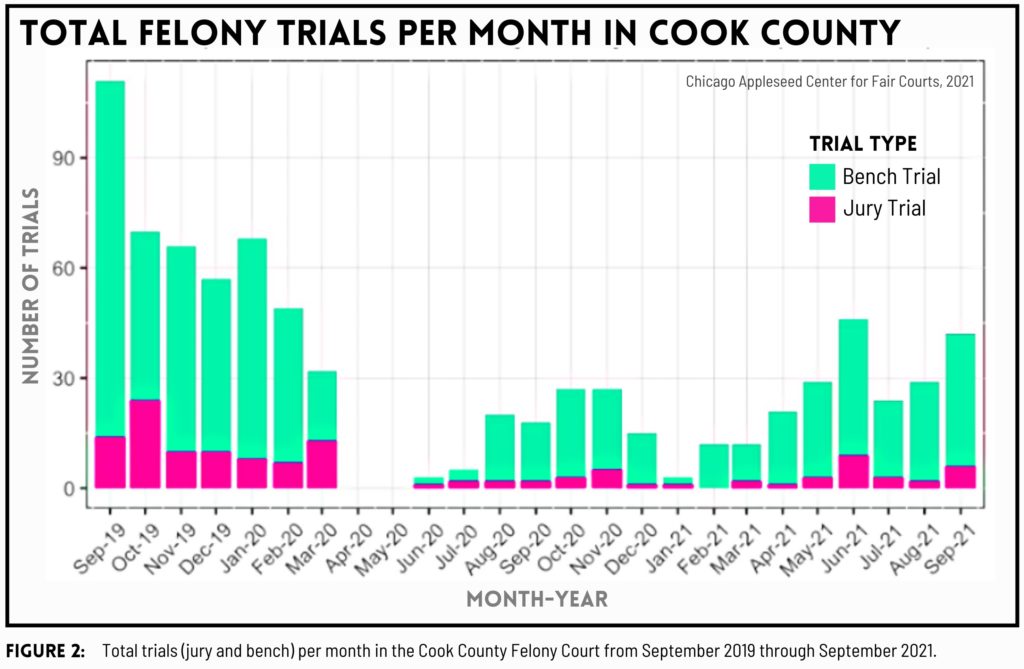

Trials have rebounded at a slightly slower rate — no doubt because distancing requirements still reduce the number of trials that can be held at a time. As shown in Figure 2, the majority of trials that take place in Cook County are bench trials, but jury trials have also been taking place with nine in June and six in September of this year. While the monthly numbers of jury trials are still lower in 2019, these rates represent a significant step toward reducing the backlog.

Most encouragingly, the number of people incarcerated pretrial — both in the Cook County Jail and on house arrest — has been steadily dropping (although these populations are still as high or higher than they were before the pandemic).

The current jail population is about 200 people fewer than its height in August, when over 6,000 people were in Cook County Jail for the first time in years. The electronic monitoring population has had an even more dramatic decrease: the number of people incarcerated in their homes has fallen by almost 700 people since its height this summer of over 3,300 people. Though there is still much work to be done, the reductions in the number of people incarcerated is encouraging.

All in all, the Cook County Courts should be commended for their ability to substantially accelerate court operations after the announcement of the October 1 reinstatement of speedy trial rights. Efforts over the summer and into the fall put the Courts in a much better position to safely continue to operate during the pandemic, while also appropriately respecting accused people’s constitutional right to a speedy and fair trial.

If there is one lesson to be learned from this ordeal, it is that clear, definitive guidance from the Supreme Court may have helped get the Cook County Courts back on track. Although there were many reports of a growing backlog of cases during 2020 and 2021, it was not until June of 2021 — when the Illinois Supreme Court announced the reinstatement of speedy trial rights — that the felony courts were successful in substantially accelerating their operations. We hope this can serve as a guide for the future to show that it can be helpful for higher courts, whether they be appellate courts, the Supreme Court, or Chief Judges Offices, to give firm, clear guidance on court operations so that the complex system is collectively motivated to efficiently solve problems.