UChicago Crime Lab Report: Blaming Electronic Monitoring for Violence is Not Supported by the Data

Electronic monitoring (EM) is a form of incarceration in which a person is ordered to wear an ankle shackle that records their location. In Cook County, the Sheriff runs a pretrial electronic monitoring program that combines location monitoring with house arrest. Individuals charged with crimes—who are presumed innocent until proven guilty—are confined in their residence with an electronic device monitoring their location. Any unauthorized absence from the home is grounds for immediate re-incarceration in the county jail.

Despite these stringent rules for people on house arrest, participants in the program have frequently been scapegoated by politicians who are seeking easy answers to questions about crime and violence. Chicago’s Mayor Lightfoot has often criticized the use of electronic monitoring for those she considers “violent and dangerous people.” But blaming electronic monitoring for a rise in violence is simply not supported by the data.

Mayor Lightfoot has been eager to “sound the alarm about the growing number of pretrial offenders released back to the communities in Chicago on electronic monitoring” despite this lack of evidence. In January of 2022, she cited police records showing the number of people arrested on electronic monitoring for a “violent offense”; amounted to less than 1% of all individuals on electronic monitoring in Cook County. The Chicago Tribune found the Mayor made a number of inaccurate statements regarding alleged violence committed by individuals on electronic monitoring – including blaming the murder of a seven-year-old on electronic monitoring, when the men charged were not, in fact, on EM when she was killed.

Chicago Police Superintendent David Brown has also blamed electronic monitoring for a rise in violence, claiming in a 2021 meeting with Chicago City Council that there has been “an explosion of violent offenders being released back into our communities on electronic monitoring” and citing examples of individuals on EM who had committed shootings. These examples are good for fear mongering, but represent a small fraction of those on electronic monitoring. In fact, the rates of people who are arrested for new crimes while on Electronic Monitoring is similar to the rate of pretrial re-arrest for people not on monitors.

News outlets have been eager to join politicians in this narrative, too. The Chicago Sun Times editorial board wrote an article in April 2022 titled, “Get Rid of ‘Essential Movement’ in Electronic Monitoring for Suspects in Violent Crimes,” and Fox News wrote, “Chicago Murder Suspects Reportedly Roam Streets on Electronic Monitoring at Alarming Rate,” a piece in which Chicago Alderman Raymond Lopez incorrectly claimed (regarding broader criminal justice reforms) that “thousands have been shot in the name of politics.” These sweeping statements have become all too common talkings points about violence in Chicago, despite being largely disproven.

For those who wish to make evidence-based conclusions about electronic monitoring, there are two important points to keep in mind when hearing this type of rhetoric:

- First, data has never supported the idea that people on electronic monitoring are causing an increase in violence – and new data analyzed by the Chicago Crime Lab makes clear that there is no connection between people on EM and rates of violence. Laws and judicial decisions should be based on research and data, which shows that the vast majority of people on pretrial EM in Cook County do not commit violence on EM – regardless of scapegoating and fear mongering by local politicians.

- Secondly, all people are innocent until proven guilty in a court of law. People on pretrial electronic monitoring should never be treated as convicted criminals. Many people on electronic monitoring will, ultimately, be found not guilty of the acts they are accused of or will have their cases dropped – and nearly all of them will continue to be our neighbors after their cases are resolved through sentences of probation and other forms of community supervision.

In May 2022, the Chicago Crime Lab, a think tank known for its work with law enforcement, published a report that undermines any claim that people on electronic monitoring are driving an increase in violence in Chicago. The report first examined the rates of people arrested by Chicago police while on electronic monitoring. It is important to note that the vast majority of people who are placed on Electronic Monitoring are not rearrested for any crime. The Crime Lab found that even among the sliver of electronic monitoring participants who are rearrested while on house arrest, the percentage arrested for violent crimes is low, and the rate of re-arrest for the shootings and homicides cited by the Mayor is miniscule.

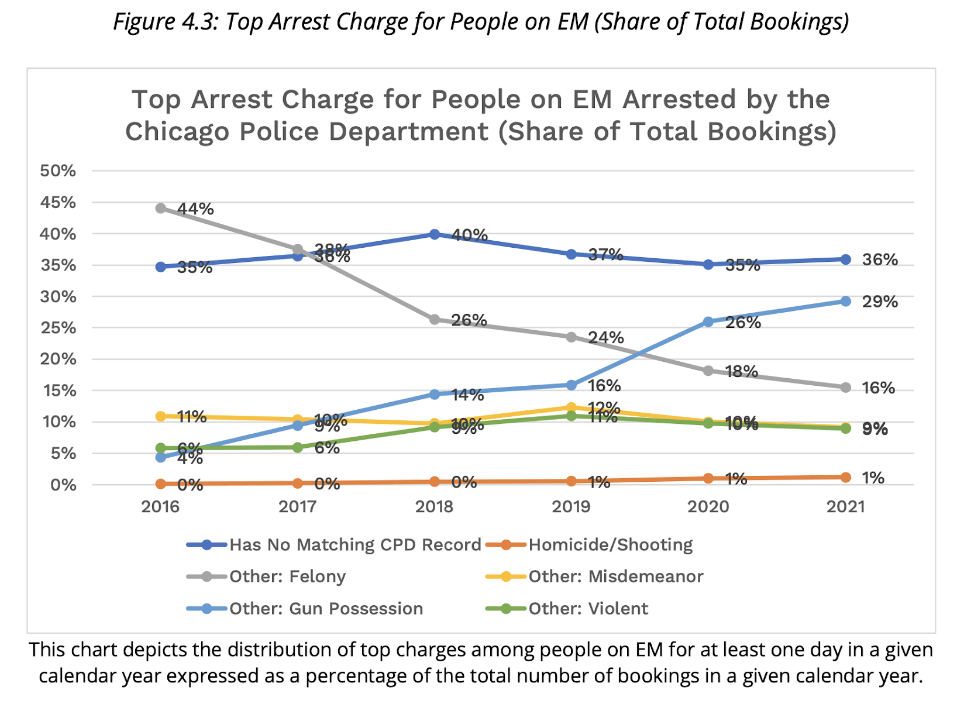

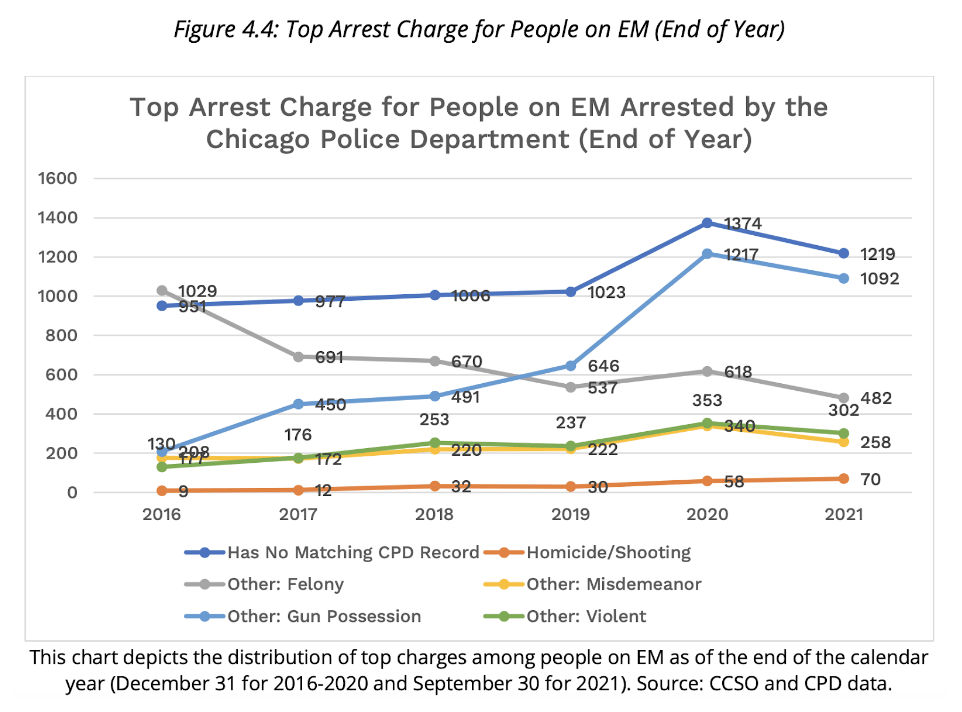

Figure 4.3 from the Chicago Crime Lab report’s data appendix shows a snapshot of one day in each calendar year, and shows the number of people on electronic monitoring for violent crimes in total is 9%, while the number of people for both shootings (non-fatal and fatal) and homicides combined was just 1%. In total, only 70 people were on electronic monitoring for shootings and homicides combined in 2021, as seen in Figure 4.4, from the same report.

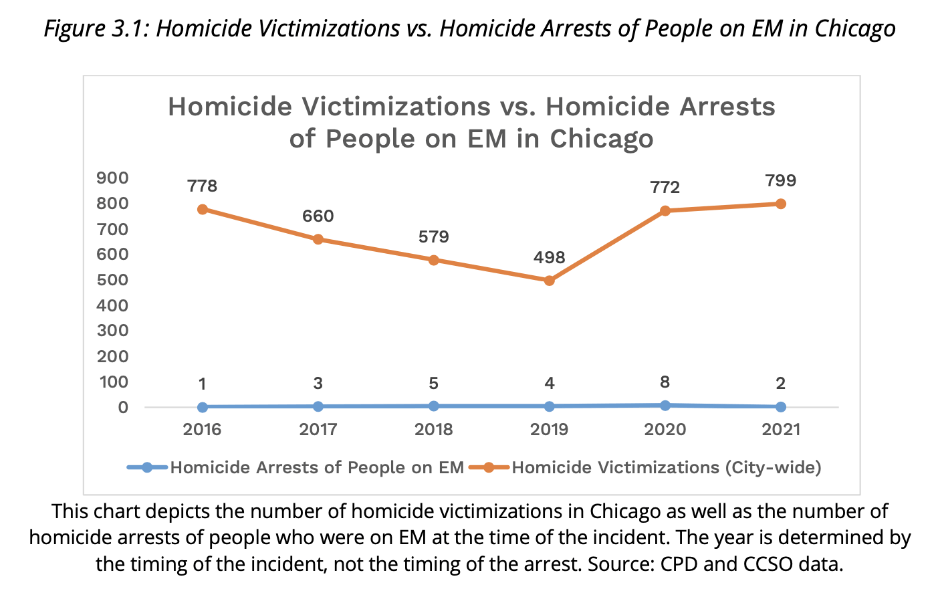

The Crime Lab report then compared homicide victimization to homicide arrests for those on electronic monitoring (Figure 3.1). Those numbers for 2021 are 799 homicides, and two arrests for individuals on electronic monitoring. Even in the year with the highest number of homicide arrests for those on electronic monitoring (8 arrests) that accounted for only about 1% of all homicides city-wide.

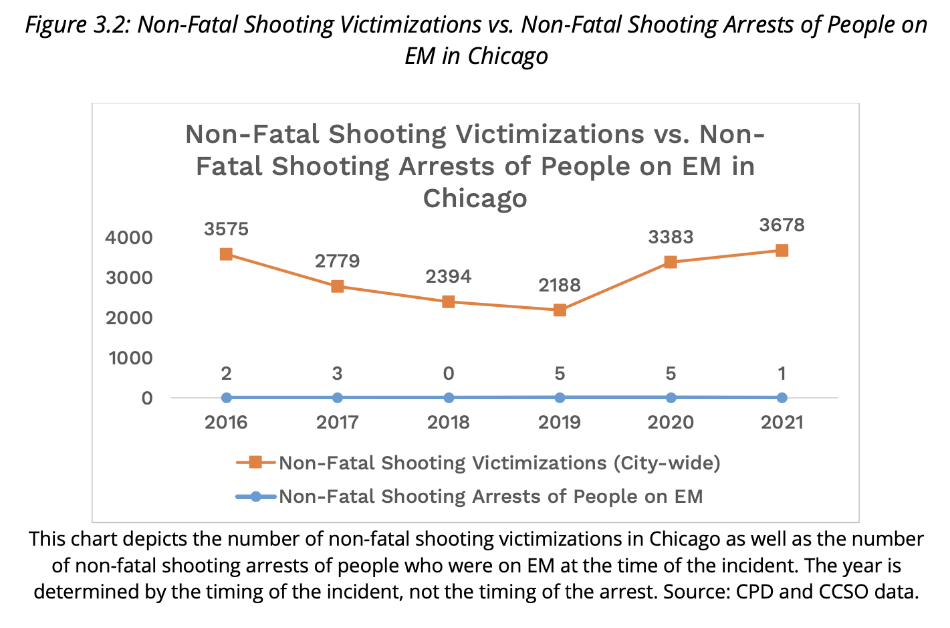

When we consider non-fatal shootings, as shown in Figure 3.2, again from the UChicago Crime Lab report, there was only one arrest of someone on EM for a non-fatal shooting out of a total of 3,678 city-wide in 2021.

It’s also important to put the rise in homicides in Chicago in 2020 and 2021 in context. This increase has occurred—and continues to occur—in other cities as well; it is, unfortunately, a national trend, with gun deaths (including death by suicide) increasing 14% in 2020 overall. Cities such as New York and Los Angeles saw an increase in homicides from 2019-2020, with New York increasing from 319 to about 500 and Los Angeles seeing 351, increased from 258. Cities including Albuquerque, Memphis, Milwaukee, Tulsa, and Des Moines saw record numbers of homicides in 2020. Some of these cities have large electronic monitoring programs, while others do not. The rise in violent crime across the country was likely driven by the same root causes of life disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic; blaming changes in the Electronic Monitoring program in Chicago alone ignores larger trends and evidence.

According to criminologists, this increase in violence has likely been caused by economic and social stresses, which have been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The pandemic has caused an increase in social isolation and negatively impacted mental health, resulted in children and teens being out of school, and increased poverty, unemployment, and overall economic uncertainty for many. At the same time, gun ownership spiked, with purchases increasing 64% from 2019-2020. These factors combined to create a nationwide spike in violent crime, which Chicago was affected by.

Although it is easy to scapegoat people accused of crimes, criminal justice policy should be based on data, not on political rhetoric. Our policy decisions must respect the presumption of innocence, and grant people accused of crimes as much freedom as possible while they await their day in court. The conversation around electronic monitoring in Cook County should be focused on whether it is necessary at all to confine people to their homes pre-trial, and on ways to make the program as humane as possible. Ultimately, scapegoating people released pretrial will do nothing to prevent crime. We must focus on root causes of crime and invest in our communities if we want to see a reduction in violence.

This post was researched and written by Law Student Intern, Tessa Weil Greenberg, a rising 3L at Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law.